Women who do things

The story of Esther Wheelwright and the communities of women and girls who surrounded her

An offhand remark can change everything. I still remember a graduate school professor’s consternation at the idea of “women’s history.” “They don’t do anything,” he protested. The comment passed without notice in a room full of male professors and students, but it took up permanent residence in my head. I was hooked, not just by his attitude problem but by the nagging reality that in the categories this well-regarded historian recognized—wars and politics and all that—he was right.

Writing women into history isn’t easy. It’s one thing to add an occasional sidebar in a textbook or praise a heroine whose brave exception proves the rule, but that doesn’t change the overall story line. The narrative still belongs to men who “do things,” driving the engines of change by waging wars and winning elections.

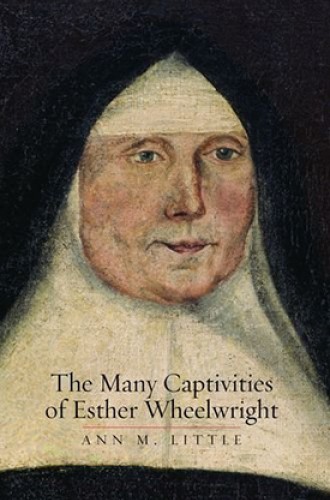

Ann M. Little, who teaches history at Colorado State University, has taken on this challenge. Her massively and meticulously researched biography of Esther Wheelwright—born of Puritan stock, then Wabanaki captive, and finally French Catholic nun—is a story of politics and war in 18th-century North America, with women at the center. Much of the landscape is familiar: conflicts between colonial powers and cycles of frontier violence. But ultimately this is a story of one woman and, more importantly, the communities of women and girls “who surrounded her at every stage of her life,” Congregationalist, Wabanaki, and Ursuline.