Why existentialism still matters

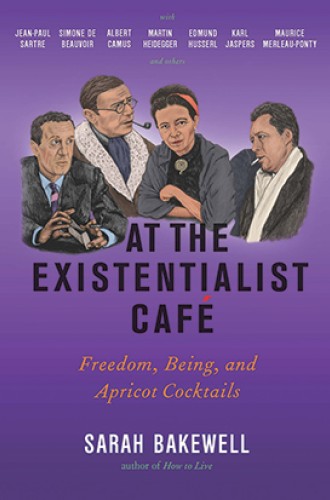

Sartre, de Beauvoir, and Camus have something to say about living authentically.

Existentialism, which was all the rage in Europe and America in the late ’40s, ’50s, and early ’60s, has lost much discernible meaning. One rarely even hears the term these days. In our age of terror, one is most likely to encounter existential used in claims of “existential threats” to national security that call for the relaxation of moral scruples against torture, assassination, and the slaughter of civilians. Jean-Paul Sartre would not be amused.

In the United States, no one threw the term existential around in careless fashion more than Norman Mailer, the one American author who explicitly assumed the mantle of “existentialist” and held a significant role in ushering existentialism into the twilight. When I was in college at Yale in the early ’70s, my friend Mark Singer (now a longtime staff writer at the New Yorker) was working on a senior thesis on Hemingway and Mailer as journalists. Mailer came to visit the campus, and Mark eagerly attended a dinner in his honor, hosted at Calhoun College by the critic and literary biographer R. W. B. Lewis.

Here is Mark’s account of the event: