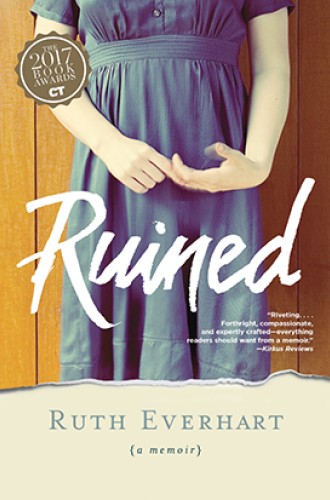

When theology fails

After Ruth Everhart was raped, she had to rebuild her beliefs about God’s will.

Ruth Everhart’s memoir is prefaced by a publisher’s note warning that the book may offend because it includes violent events and vulgar language. I confess that as I read this, I chuckled darkly. It seemed unnecessarily apologetic. As the back of the book reveals, it’s the story of the night in Everhart’s senior year of college when two armed assailants broke into her college apartment and raped her and her roommates at gunpoint. The least a reader can do, in response to the critical witness Everhart provides, is to shift uncomfortably in her seat.

As it happens, Everhart is a careful narrator. There is nothing salacious about her telling of the events of that night or the process of grief, fear, and reorientation that followed them. The experience of reading her story is difficult, but there are no unnecessary details: this is neither a true-crime novel nor a sensational tabloid report.

Though the statistics were different in 1978 when the crime was committed, the sexual violence Everhart reports was unusual even for that time. She and her apartment mates were “perfect victims.” No one could have suggested that alcohol consumption or anything about their attire “contributed” to their assault: they were home, asleep. Everhart wore a long, flannel nightgown. This crime was also unusual in its randomness. A 2014 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that the vast majority of victims of sexual assault know their rapist; rapes by strangers make up only 12.9 percent of those reported.