The Till family’s agony

Carolyn Bryant changed her story. Does this change the meaning of Emmett Till’s death?

When Emmett Till, a 14-year-old black boy from Chicago, was murdered for allegedly whistling at and touching a white woman in the Mississippi Delta in 1955, his story became a cornerstone of the civil rights movement. This was due in great part to his mother, Mamie Elizabeth Till-Mobley, who insisted that his hideously mutilated body be put in an open casket for all to see. According to the Chicago Tribune, more than 40,000 persons viewed the body.

In 2004, Till-Mobley’s book about her son’s murder, Death of Innocence, was published. A dozen others followed. Just last year, for example, Devery S. Anderson published Emmett Till: The Murder That Shocked the World and Propelled the Civil Rights Movement, which is now being turned into an HBO miniseries produced by Jay Z and Will Smith.

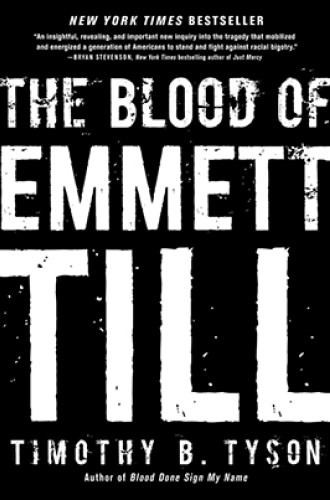

Timothy Tyson’s The Blood of Emmett Till has been launched into the national spotlight for its revelation that the woman who accused Till of harassing her, Carolyn Bryant, admitted in an interview with the author that she had been lying.