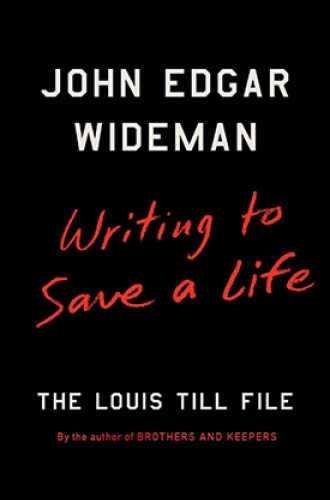

Inventing a voice for Louis Till

John Edgar Wideman counters the official record of Emmett Till’s father with a more empathetic version.

“Wrong color, wrong place, wrong time.” This is John Edgar Wideman’s conclusion about the death of Louis Till, Emmett Till’s father.

Wideman, a novelist and essayist, was 14 when another 14-year-old black boy, Emmett, was murdered in Mississippi. In this book, Wideman has written an account not of Emmett, but of his father Louis, who was killed while serving in World War II.

Wideman uses the twin deaths of father and son to explore father and son relationships, the conjunction of racism and family life, justice and injustice, truth and its deliberate destruction. Writing to Save a Life is a mix of memoir, biography, history (and an acknowledgment of history’s failures), imagination, and cultural commentary, as Wideman tries to piece together what happened to Louis while he served in the army in Italy.