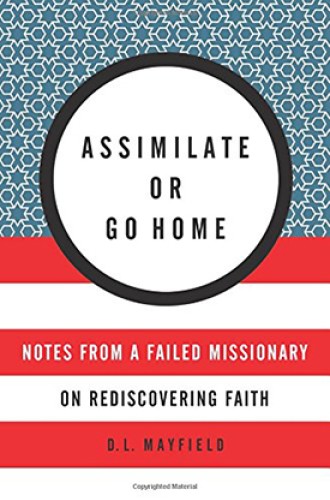

A do-gooder’s tale

D. L. Mayfield wanted to help Somali refugees. She ended up mostly baking them cupcakes.

Most of the essays in this artfully composed collection are structured according to the same plot: a well-meaning missionary is turned inside out and upside down by the harsh realities of the mission field. At first read the repetition grated. I expected D. L. Mayfield to provide an overarching story, a narrative thread. I wanted the narrator to play the part of protagonist, overcoming hardship to claim victory in the end. But this isn’t how it works, especially not for a self-avowed “failure.”

At one point Mayfield reflects upon her missionary colleagues who have been at work far longer than she, the people who have “seen stories as they really are: long term and full of miracles and crushing disappointments, a constant tale of being saved and relapsing back into ourselves.” These are the kinds of stories Mayfield tells. You don’t get from her happy endings and tidy morality tales. You get theological and ethical ambiguity. You also get extremely uncomfortable with your own extremely comfortable life (if, like me, you are a reader who lives with relative privilege).

Mayfield presumed as a child that her missionary aspirations would take her overseas. Instead, she finds herself involved—an insufficient word if there ever was one—with the Somali Bantu refugee community in her hometown. As is frequently the case with vulnerable and economically disadvantaged groups, the refugees who land in Portland, Oregon, land in the margins.