Zora Neale Hurston brings us the voice of a former slave

Hurston's singular ear for the beauty of speech and memory brings Cudjo Lewis's story to life.

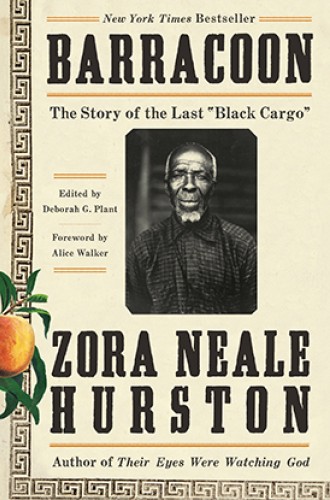

About the African slave trade, “the most dramatic chapter in the story of human existence,” Zora Neale Hurston writes, the justifiers of slavery have had much to say. But the Africans themselves have not been heard from. “All these words from the seller, but not one word from the sold,” she writes in her introduction to Barracoon. The book, written by Hurston in 1931 and unpublished until this year, is her attempt to save some words from the sold. It recounts the story of Oluale Kossola, also known as Cudjo Lewis, the last survivor of the last slave ship.

The ship’s legend is so crass and shocking that it could easily be mistaken for satire: “In April of 1858, while traveling about the Roger B. Taney”—named for the infamous chief justice of the Supreme Court who’d authored the Dred Scott decision a year earlier—a man named Tim Meaher made a bet “that he could bring Africans into the country in spite of the ban against trans-Atlantic trafficking,” with no one being hanged for the crime. Bet or no bet, Meaher imported slaves from the Dahoman port of Ouidah the following year. He and his partners were charged with piracy but not convicted, and the last “black cargo” of the antebellum era was never returned home.

Hurston met Kossola in 1927 when she was a student of anthropologist Franz Boas and working for the “father of black history,” Carter G. Woodson. A brief journal article was the only outcome of their initial meeting. With funding from Charlotte Osgood Mason, a major patron of the Harlem Renaissance, Hurston was able to return and spend an extended period recording Kossola’s recollections.