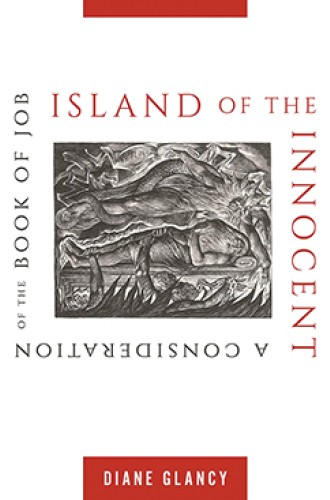

The woman who haunts the book of Job

In Diane Glancy’s poetry and prose, the cries of Native Americans echo the laments of Job’s wife.

As Diane Glancy studied the book of Job while creating this collection of original poems and poetic prose, she realized that the biblical text was haunted. Suffering and loss experienced by Native Americans seeped out. Stories from her own Cherokee ancestry streamed between the verses, overlaying and recoloring the narrative, bleeding out historically distant and emotionally immediate meaning. She writes, “The particular poetics of the lamentations of Job in Uz and the Native American on the North American continent are my heritage. A personal sense of loss.”

Glancy’s book fills gaps of understanding and probes instances of suffering in a creative composition that keeps readers rocking forward in anticipation of another interpolation or surprising insight. Researched facts, explanations of the author’s literary intentions, and presuppositions of her mind are set between her poems. These bridges of language lead back and forth across time and space, turning in and out through the poet’s biography.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

One of the language fragments states that there is an “energy-field in poetics.” Glancy’s book transfers the energy buried in the book of Job, compressing emotion from the story, splintering conventional interpretation, and redirecting attention from the text here and there—to Custer’s Last Stand, to the author’s emotional memories of her family, to the dreamscapes of highway travel. She writes: “Poetry is cartography. An imagined mapping of the wilderness for an understanding of the wilderness, or as much of the wilderness as can be understood.”

Glancy’s words wedge into spaces between knowledge, memory, piety, and history, probing and filling the gaps: “Poetics separates the bone from the marrow—Hebrews 4:12. It separates the words of a sentence. It makes known the things between.” The seams in the story of Job’s inexplicable suffering meeting God’s inscrutable ways open to “the haunting experience of poetics. The writing of it. The reading.”

This volume is the first in Turtle Point Press’s Joan Books series, which aims to highlight “the experiences, insights, and wisdom of bold and outspoken women.” The bold woman who appears in Island of the Innocent is Job’s wife. Largely absent from the biblical text, here she is introduced under the name of Jehorah, with this sure and startling line: “It was her house too.”

Brought out from the silences of the original oral versions of the story, and from the spaces between the words of the received biblical text, Jehorah fills out the emotional drama of Job with raw and creaturely outbursts. Job is “a self-satisfied, humanitarian snob who finally saw his meagerness before God.” Jehorah, without an invitation to address God, rages at the suffering she and her household endure. She cries out in frustration at the tragedy around her. She roars and shouts at the injustice and the inexplicable pain. “Jehorah represents the times we suffer and don’t understand why.”

Island of the Innocent reads like a pilgrim road trip, with poetics the method of travel. Unusual and satisfying, the book moves forward haltingly in language that reflects both Job’s “muttering in his suffering” and the vocalizations of early Native American poetry, one of the subjects of Glancy’s teaching career. She writes that “early Native poetry/song came as abstraction—as parts separated from the whole. As dreams which were often considered more reliable than what could be seen.”

Glancy locates her own ancestry between Cherokee and European heritages. A worker in words from both backgrounds, she collects shards of songs splintered by time, picks up pieces of truth scattered along the highways of history. The words she works with live as individuals, with personal histories. In combination with others, each word creates meaning according to convention, rules, and customs: “Language is both the creator and the world it creates. Language is the revealer and the revealed.”

In a prose poem near the end of the book, Glancy writes, “Maybe the Lord still speaks to us in prophecy in the voices of others.” The prophet is God’s poet. Her words are fresh, bright with current meaning. Her words are old, thickened with layers of historical use.

The book’s title is taken from Job 22:29–30 (KJV): “When men are cast down, then thou shalt say, There is lifting up; and he shall save the humble person. He shall deliver the island of the innocent: and it is delivered by the pureness of thine hands.” Glancy notes that the phrase “island of the innocent” disappears in later translations, another absence for the poet to investigate. “Where is the island of the innocent?” she asks as a theological and a lexicographical question. Near the end of the book, a lonely line ends a page of abstract prose, “There is no island of the innocent,” leading back to the wisdom journey, through the shifting landscape of language.