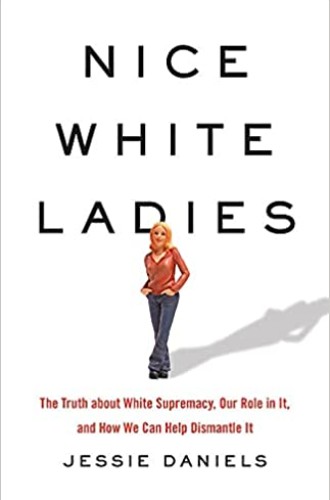

A White woman takes on the problem of nice White ladies

Sociologist Jessie Daniels reckons with the dangerous implications of the person she was raised to be.

Sociologist Jessie Daniels was originally named Suzanne Harper. Suzanne means “white lily,” and she inherited the name Harper from a grandfather who was active in the Ku Klux Klan and an abuser of children.

When preparing to publish her first book, Harper could not stomach doing so under her current name—so she changed it. But she was no Rachel Doležal, who appropriated the West African name Nkechi Amare Diallo, or Jessica Krug, who took the Afro-Caribbean name Jess La Bombalera. Harper knew that a name change is about positionality, so as a White woman from Texas, she took the name of another White woman from Texas. She became Jessie Daniels, named after anti-lynching activist Jessie Daniel Ames.

I like to imagine that the compelling and vulnerable Nice White Ladies is a candid conversation between Suzanne, the white lily raised to be a nice White lady, and Jessie, the radical lesbian feminist who embraces Flavia Dzodan’s conviction that her “feminism will be intersectional, or it will be bullshit.” In this book, Daniels reckons not only with the cultural scripts of Whiteness that pervade everything from politics to property ownership to popular culture but also with what it means to be Suzanne. She connects what W. E. B. Du Bois called “the mental wage of whiteness” with her mother’s death by suicide. This book is in some ways Jessie refusing to be Suzanne, and it is also a refusal of her mother’s tragic fate. Reckoning with Whiteness is a matter of survival, a way to seek freedom from the intergenerational racism fed to her and so many others like poisoned milk.

Daniels’s personal stake in this work is what makes Nice White Ladies both authentic and grounded. Perhaps intentionally, she bombards readers with a dizzying number of examples of nice White ladyhood, from Ellen DeGeneres to Gwyneth Paltrow to Elizabeth Warren to monstrous Karens. These nice White ladies, according to Daniels, “all work to make a particular kind of white-hetero-lady-identity seem natural and in need of care.”

Daniels names this White ladyhood a death cult, as seen in the carceral feminism of Mariska Hargitay’s character in Law & Order: Special Victims Unit. She also calls it a war machine. When, in Central Park, Amy Cooper calls 911 and “performs fear” for the dispatcher against a Black man, Christian Cooper, Daniels says her body “becomes an assault weapon.” Nice White ladyhood is a deadly performance.

While Daniels gives many extreme examples, she also continuously connects this nice White ladyhood to her own family. It is important that Daniels employs the concept “raised white” throughout her book, as opposed to “being white.” Here, the sociologist behind the book shines. Whiteness is not framed as fixed or static but rather as a technology, a kinship bond, and a repeating process of socialization that, no matter how often it claims to be nice, is anything but.

The three words of her title—nice, White, and ladies—explain this dynamic. Niceness is the DeGeneres brand of avoiding public confrontation. Through the troubling tale of Patty McCloskey, who in 2020 pointed a gun at Black Lives Matter protesters marching past her house in St. Louis, Daniels describes niceness as being well educated, professionally employed, upper-middle class, heterosexually married, and a mother. This niceness comes with a loaded gun. “The underbelly of the ‘niceness’ is the harsh commands of the slave mistress,” she writes.

Daniels deftly describes what this kind of niceness does, but I wish she had offered a clearer definition of the word, as she does with both White and ladies. I have difficulty equating McCloskey’s actions with niceness.

Daniels’s definition of White, however, is crystal clear: “This way of being . . . goes deeper than simply bias or prejudice. It is rooted in who we feel connected to, where we feel safe, and how we move through the world.” She names how this process requires adherence to the gender norms and relationships that characterize White dominance. If family is created by drawing a circle around the people we care about, for White people that circle becomes a border wall to keep in intergenerational wealth and social normativity—and to keep out those beyond the pale. The circle of Whiteness is real, and at the same time it is a lie.

When Daniels writes that “whiteness is the lie that is killing us, and the lie is gendered,” she brings us to the final word of her title: ladies. Here, Daniels excels in a queer analysis of Whiteness. Though she claims her book is not a calling out as much as it is a calling in, in fact she does both. She calls out the failures of gender-only feminism predicated on particular body parts with particular tones, rejecting the “vagina feminism” that reinforces gender as a fixed idea and buttresses binaries, be they male/female or White/other.

She concludes, “White supremacy has always included, either implicitly or explicitly, a heteronuclear family agenda that rests on the destruction of queer lives.” Here, Daniels is not so much queering antiracism work as she is revealing the inherent queerness in the struggle against Whiteness. I believe this to be the most original, brilliant, and needed contribution of her book.

While Daniels offers practical tools for what she calls “swerving away” from the supremacy of Whiteness—one of which is love-centered spiritual care—I find the careful questions she raises throughout to be even more effective tools. She addresses these questions to White women:

How did we, white women, help create a world that gives us this lethal power? Why do we often feel afraid and entitled to protection? . . . Could it be that there is something in being raised white that damages us and that we look to recover in self-care? . . . What if self-care for white women looked like processing guilt and learning to metabolize the shame of white supremacy? . . . How do [we] focus a critical lens on the power of whiteness without white people sucking all the air out of the room?

I’ll add some theological questions to Daniels’s. How has Christianity needed and nurtured nice White ladyhood? What would a church divorced from nice White ladyhood, and all the normativity that entails, look like?

Nice White Ladies is a deeply personal and culturally relevant story of the ways Whiteness and womanhood are conjoined, a breeding that deals death both to those who are excluded and to those within that troubled family. It is also the deeply personal and culturally relevant story of a Texan lady named Suzanne who decided she did not want to be a delicate white flower any longer. Though her Whiteness can never really be shed, she has learned and claimed—through heartbreak and therapy and the creation of new kinship ties—that her name is Jessie. And she is trying her best to live up to it.