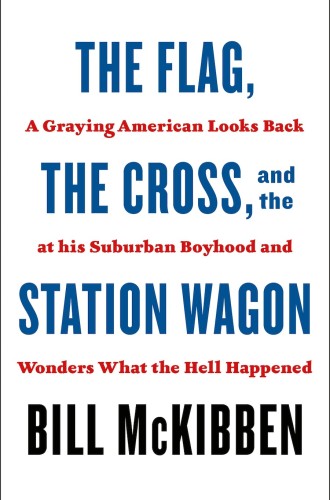

Where did the baby boomers go wrong?

Bill McKibben recalls his suburban childhood without a hint of nostalgia.

When Bill McKibben describes what it was like to grow up in Lexington, Massachusetts, a bucolic bastion of privilege outside Boston, it sounds so idyllic that it almost seems like a parody of life in affluent suburbs at that time. His family lived in a comfortable house on a quiet and leafy street named Middle Street. He attended an excellent public school (currently rated number one in the state). During the summer, he gave tours of the Lexington Common—the site of the “shot heard ’round the world,” the opening shot of the American Revolutionary War—wearing a tricorn hat, regaling visitors with stories of the historic events that took place there. McKibben writes that, through that experience, “I came by my patriotism honestly.”

On weekends he attended a thriving mainline church, which sat proudly on the same common. He was active in the church youth group, went on retreats and service trips, and sang “Kumbaya” around campfires without irony. McKibben summarizes, “We were as statistically average as it was possible to be.” Well, average if you consider only the upper-middle-class stratum of American society.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Although there were aspects of growing up in his hometown that he still appreciates, McKibben makes it clear from the beginning of this book that he is not succumbing to nostalgia. He recognizes in retrospect that in that idyllic setting the seeds of economic and racial inequality—as well as of the climate crisis—were already sown.

McKibben gives a number of anguished examples. Based in part on its history, Lexington prided itself on being a force for enlarging the scope of justice. In 1969, there was an initiative to increase the lower-income housing in the town. Although some citizens expressed concern that having such housing might attract the “wrong kind” of people, the town meeting—the local governing body—gave its blessing by a vote of 127–56. In an editorial, the local paper crowed, “Lexington citizens, like their forebears, still believe in ‘liberty and justice for all,’ and are ready to support the practice, as well as the principles, of fair housing.”

When it came time for a town-wide referendum, however, the housing initiative was defeated by a margin of two to one. The views expressed in public and the opinions reflected in the voting booth diverged dramatically. This is not an uncommon phenomenon, but it does cause one to wonder what else might lurk behind the various kinds of attractive façades that are prevalent in a place like Lexington.

During the 1960s, the station wagon referenced in the book’s title was the ubiquitous symbol of suburbia, occupying the space occupied by SUVs today. Station wagons made suburbia possible. They also seemed to express the emerging spirit of America that was embodied in suburbia: the ascendency of the individual and the nuclear family at the expense of the wider community. In the city, many people can live in the same building and use a common mode of public transportation. In the suburbs, houses are detached from one another, as are the means of transportation. Suburban houses and cars both reflect and contribute to a kind of atomistic approach to life. As if that weren’t enough to attract McKibben’s ire, station wagons are also gas-guzzlers, contributing to the climate crisis that he has spent most of his career addressing.

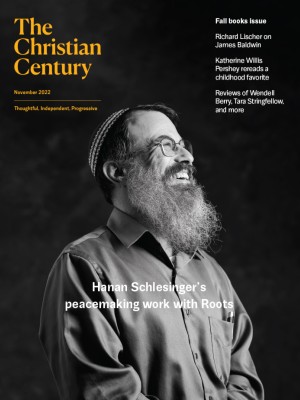

Of the three aspects of society alluded to in the title—country, church, suburbia—church gets the most sympathetic treatment. McKibben honors the role religious leaders played in what he calls, “the last ‘justice moment’ in American history,” the fight for civil rights and against the Vietnam War. He profiles a couple of clergy he has known who have acted with courage and conviction, and his words exude genuine admiration.

Nevertheless, the words of appreciation are mixed with a kind of wistful critique. The church of McKibben’s youth was firmly and obviously established in the culture at large. And that, he concludes, was a problem. “As with most establishments, this one was . . . dull, almost as a matter of principle.” An established church has to be all things to all people: “If you’re the culture, you can’t be the counterculture.” In our current era of increasing disestablishment, McKibben sees an opportunity for the church to become again a countercultural community, one that is better positioned to be a countervailing force to the malignant individualism he sees as the root of so much that ails us today.

This book is a compelling cri de coeur to McKibben’s fellow baby boomers. In fact, it is hard to imagine recommending this book to anyone else. He addresses us boomers as if there were no one else in the room. He quotes assessments of boomers from people of younger generational cohorts, none of them flattering, because he thinks we need to hear them. He concludes that these criticisms are largely justified, leading to the confession: “We were better consumers than citizens.”

Now, as boomers are retiring in huge numbers, McKibben challenges us to stay engaged, but he is clear about what our role should be: “Not to lead: the leaders of work for change are younger people, who have risen to the occasion. But they need backing; they need our third act to improve on the second.”

One of the common traits of boomers is that we are used to being at the center of the action. McKibben is clear that now we need to play a supportive role for younger leaders. For once, we must take a back seat. Just not in a station wagon.