When Christian practice (de)forms us

Do practices make us better people? Lauren Winner isn't so sure.

Recall a jarring scene in The Godfather: Michael Corleone, poised to take over the family business, is making vows as the godfather for his new nephew. “Do you renounce Satan?” the priest asks. “I do renounce him,” Michael affirms. “And all his works?” “I renounce them.” “And all his pomps?” “I do renounce them,” Michael enunciates.

But spliced between these renunciations and Michael’s credo are scenes of ghastly killings carried out on Michael’s orders.

Maybe liturgy isn’t as formative as some theologians have suggested. Maybe Christian practices aren’t as effective as some would have hoped.

What’s particularly heartbreaking, of course, is that we don’t need fiction to imagine this contradiction. The heinous pattern of abuse in Catholic dioceses in Pennsylvania is even more chilling than Coppola’s gore. The steady stream of abusers unveiled by courageous #MeToo victims is bringing the dark side of the church into the light. The daily complicity of white Christians in systemic racism and even eager ethno-nationalism suggests the practices of the Christian faith aren’t doing what we thought.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

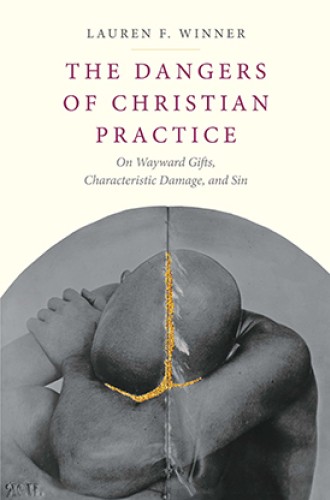

This complicated reality—we might call it “the Godfather problem”—is the target of Lauren Winner’s incisive, complex book, The Dangers of Christian Practice. Her argument lands on both academic and pastoral trends. As she wryly notes, “in some scholarly communities, to designate a study as a study of ‘practices’ is to cast a rosy glow.” This has been particularly true in postliberal theology over the past couple generations, as the insights of Alasdair MacIntyre informed the influential work of Stanley Hauerwas, who, in turn, has made a huge dent on an entire generation of Christian theologians who have looked to the practices of the church as a resource for staving off our cultural capitulation to the forces of consumerism, nationalism, and militarism. (The Blackwell Companion to Christian Ethics, a widely used textbook, gathers this school of thought between two covers.)

Winner also points to a veritable industry of “practices” literature directed at practitioners and parishioners, including the influential work of leaders like Dorothy Bass and Craig Dykstra. Indeed, I think Winner would include some of her own work here, and I too should add a mea culpa.

“What unites these projects,” Winner observes, “is that in each, practices have been embraced as a way of fixing something in or for the church; practices have been embraced as a strategy of recuperation, repair, or reform.” When Protestant theologians write about Christian practices, “they are almost always extolling the practices.” The question that never seems to get asked is: “Why carry on with habits or practices, given the likelihood of their (and our) going wrong?” What good did this renewal of practices do for Catholic children in Pittsburgh or women at Willow Creek Church?

Winner is facing up to these questions and invites the church to do the same. The heart of her analysis is the concept of what she calls “characteristic damage” (with debts to Paul Griffiths). The key point is that when Christian practices de-form us it’s not simply incidental or because they have been tainted by the world. That would be to imagine the source of deformation is always other than the church, leaving the supposed purity of the church’s practices compromised by something else.

Winner’s point is more trenchant: some deformation is uniquely generated by the Christian practices themselves. Some of the damage perpetuated by Christian practices is almost inherent, uniquely emerging from the sacred logic of those practices. In other words, when Christian practices become twisted and do harm, the contortion often reflects the kingdom curvature of the practices. Such characteristic damage reflects something about the very nature of the thing.

So helicopter parenting, for example, reflects something about the very nature of parental care; or a cliquey dinner circle reflects something about the power of meal fellowship to bind people together, which is why exclusion is an unsurprising twisting of its intent. The distortions are “familiar,” as Winner puts it. They make a kind of sad sense given the nature of the practice. They are intrinsic rather than extrinsic, latent in the practice as a lurking danger.

So, too, with Christian practices. Unexempt from the effects of the Fall, the disciplines of the faith are no less immune to characteristic damage. Winner focuses on three unsettling historical examples: the way the Eucharist funded violence against Jews in the host desecration pogroms of the late Middle Ages; the way intercessory prayer was gnarled by slave-owning women in prayer journals of the antebellum South; and the way baptism funded privatization in late 19th-century christening parties, thereby “evacuating the ecclesial into the familial.” Each case is explored with rich historical texture and theological sophistication and should equip us to extend this sort of analysis to realities in our own time. Discomfort is the goal here.

But not despair. Winner clearly isn’t out to dismiss practices. After all, what else have we got? To whom else shall we go? God has given us the gifts of these practices as the conduit of the Spirit. The point isn’t to de-practice Christianity but rather to “depristinate” practices, as she puts it.

The damage emerges in the giving, not from the Giver: “a recipient like this [like us] cannot help but damage a gift like that.” Such is the risk of grace in our postlapsarian cosmos. “What kind of God gives gifts we can’t use well?” Winner asks in the spirit of theodicy. “The God who gives felix’d gifts,” she replies: the God who risks giving gifts even to the likes of us, who can felix our culpa. Depristinating these practices can make us aware of how we damage the gifts and perhaps, by the grace of God, can be a catalyst for repentance, reform, and renewal, even as these are haunted by their own possibilities of deformation. Only the resurrection logic of grace gives hope: “even damaged gifts make possible goods that would have otherwise been impossible.”