What we can learn from medieval views of the human body

Some ideas have morphed while others have strangely stayed the same.

Several years ago, I spent a rainy afternoon at the Wellcome Library in London examining a 15th-century birthing girdle. The eagle-eyed curator watched my every move, making sure I didn’t touch the stained and disintegrating roll of parchment. Inscribed on the narrow manuscript were instructions for its use: it was to be wrapped around the body of a woman in labor with its images of Christ’s wounds to be placed on her skin and its charms and prayers recited to ensure protection during the harrowing process of giving birth.

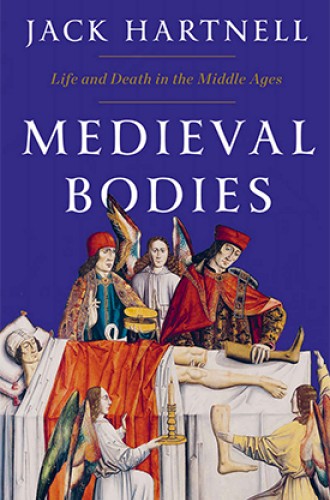

It is easy to dismiss objects like this and the culture that produced them as primitive, but Jack Hartnell suggests that they might have something to teach us if we are able to consider them on their own terms. Hartnell, an art historian at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England, does just that. Seeking to counter modern assumptions that the Middle Ages was a period of rampant superstition, dogmatism, and scientific ignorance, he offers a rich survey of medieval ideas about the human body. While Hartnell aims to make the medieval world more comprehensible to a modern audience, he also preserves the fascinating and often illuminating strangeness of the Middle Ages.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Hartnell’s book reveals a world similar in many ways to our own. Medieval people suffered from many of the same maladies as we do. Diet was considered a key to good health. Doctors successfully grafted skin, amputated limbs, and performed surgeries. People suffered from undiagnosable diseases, prayed for medical miracles, and sometimes received them. Skin color served as a means of racial and religious differentiation, denigration, and demonization. Thinkers debated the relationship between body and spirit, taking stands on such issues as when exactly life began after conception (Their answer? When the soul entered the fetus: 40 days after conception for a male fetus and 80 days for a female).

But aspects of the medieval approach to the body will also feel foreign, absurd, or incongruous to modern sensibilities. In the Middle Ages the devout meditated on images of dancing skeletons to remember their own mortality. Your local barber might also be your surgeon, if only because he already had the right tools. Fecal matter might be applied prophylactically to a wound, garlic and onions to an oozing eye, and a dead rodent might be carried as a contraceptive. The flesh of a saint’s heart could grow into the shape of a crucifix, nails, and the crown of thorns. A manuscript illumination might depict a pair of nuns picking penises from a tree or perhaps imagine a tree that flowers urine. And a king might keep a professional flatualist (Roland the Farter) on staff as an entertainer.

Navigating the familiar and the strange, Hartnell invites us to consider the complexity of medieval approaches to the body, which is never merely flesh, organs, and bones. The medieval body is both physical and spiritual, both profane and sacred. While Medieval Bodies initially may seem to be a history of medieval medicine, it is interested both in what was known of the human body in the Middle Ages and, more broadly, in what the body meant.

Hartnell treats the physical body as a jumping-off point for a wide-ranging survey of medieval culture that touches on topics as varied as courtly love, gender, sexuality, mental illness, physical disabilities, race, racism, anti-Semitism, travel, geographical knowledge, maps, the production of manuscripts, textiles, music, fashion, and food. Focusing primarily on the medieval West, the book also gestures toward the significant influence of Jewish and Muslim cultures on thinking about the body and medicine. Hartnell draws on sources ranging from medical treatises and philosophical texts to literature, religious and didactic writing, and art objects.

Like medieval medical manuals, Medieval Bodies anatomizes its subject, organizing its chapters by regions of the body, moving from head to toe. None of the ten chapters lingers long on the physical organ, instead treating the body part as a thematic touchstone for an exploration of related topics in medieval culture. A chapter on the heart begins with a discussion of bloodletting but turns into a meditation on the way in which the heart served as the center of emotion and shaped the imagery of both secular love and religious devotion. A chapter on feet discusses an amputation and offers a glance at the fashionable but impractical pointy-toed footwear of the later Middle Ages before providing an engaging introduction to medieval travel and cartography. A chapter devoted to the bones opens with a discussion of medieval knowledge of the skeletal system, which then leads into a long exploration of medieval death culture.

Each chapter displays a virtual cabinet of corporeal curiosities. Hartnell is an expert collector, with a keen sense of a good story or a compelling image and a striking ability to contextualize his sources and draw out their significance. Lavishly illustrated, the book’s color images invite us to look at human bodies anew, to see them as medieval audiences might have. While this lively book will offer few new insights to medievalists, it is an excellent general introduction to the topic, chock full of humorous, disgusting, playful, inspiring, and riveting accounts of the lives, bodies, and beliefs of people in the Middle Ages.

As strange as it may sometimes be, medieval thinking about the body reminds us of the importance of attending to the meanings as well as the material of the human body. For medieval thinkers, doctors, and patients, the human body was more like a “little world made cunningly / Of elements and an angelic sprite,” as John Donne would put it several centuries later, than like the purely physical assemblage of organs and cells that much modern medicine diagnoses and treats. Medieval bodies, like modern ones, are always more than the sum of their parts.