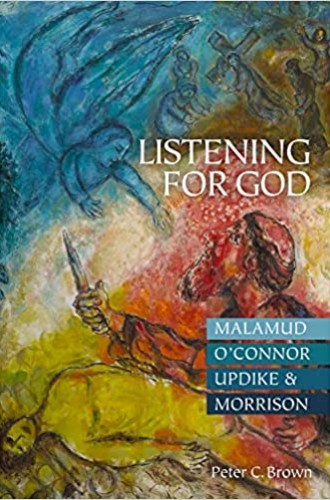

The voice of God in Malamud, O’Connor, Updike, and Morrison

Peter C. Brown’s project is urgent and personal.

“What chutzpa!” Peter C. Brown exclaims in a passage about the murderous character known as the Misfit in Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.” He continues as though he were O’Connor’s cousin: “But as Mary Flannery would say, you gotta love him. He’s just so mixed up!” In another passage, referring to John Updike’s Rabbit Angstrom character, Brown writes, “He is on the hook before the face of God. The BIG hook. The only hook that is not just human power, prejudice, prudence, or propaganda in disguise. Let’s see how he wiggles.”

With its academic publisher and its promise to explicate works by O’Connor, Updike, Bernard Malamud, and Toni Morrison, Listening for God appears to be a book for literary scholars. Yet while scholars and students will find the book useful for its take on four of the finest American authors, it is far from a mere work of literary criticism. Brown has a much more urgent and personal project in mind—as his regular outbursts of earnest and intimate rhetoric show.

He wants nothing less than to hear the voice of the wholly other God in the works of four important religious existentialist fiction writers. He convinces us that he can faintly make out that voice, which takes the varying forms of YHWH, the sternly inexplicable God of American Catholics and Protestants, and the blended European and African ideas of God crafted by formerly enslaved people.