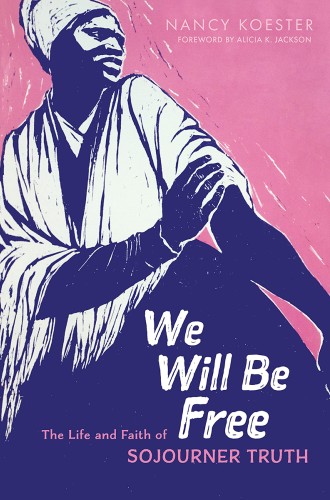

An unlettered theologian

Nancy Koester’s biography captures the remarkable ministry of Sojourner Truth, who could not read or write.

One of the few Black women I remember reading about in history class in the 1970s was Sojourner Truth. We learned that she was a former slave who delivered a famous speech, “Ain’t I a Woman?” The word theologian was not associated with Truth in my childhood textbooks, but biographer Nancy Koester adds that word to the list—alongside reformer, licensed preacher, and author. “Truth’s faith often gets ‘obscured’ when her life is seen only through the lens of social reform,” writes Koester in her excellent new biography, which is saturated with facts but still reads smoothly.

Truth ministered as a theologian, preacher, and lecturer despite being unable to read or write. She was born into slavery as Isabella Baumfree. In 1799, when she was two years old, the state of New York, where she lived, passed the first of multiple laws to abolish slavery. Abolition took effect gradually, with the emancipation of some enslaved people delayed until 1827. This approach allowed slaveholders to exploit young people like Isabella for decades. Enslaved people in New York were more isolated than in the South, with only two or three in a household. A year before emancipation was to take place, Isabella fled from her enslaver with her young infant, leaving behind three older children. A Dutch Reformed abolitionist couple purchased freedom for her and the baby.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Afro-Dutch people like Isabella celebrated Pinkster (the Dutch name for Pentecost) each year. This was a time when family members could be briefly united. One month before emancipation, Isabella was on the way to visit her older children for Pinkster when she had a vision of Jesus that inspired her to become a preacher.

Although New York slaveholders were not legally permitted to sell enslaved people to southern slaveholders, Isabella’s son Peter was sold anyway. After her vision, Isabella successfully sued for Peter’s release. She managed to secure employment as a domestic worker, but she longed to preach. Peter had a tough time adjusting to freedom and was often jailed. Meanwhile Isabella joined a church and began preaching outside of that church, initially to a group of former prostitutes.

Koester does not shy away from a bizarre time in Isabella’s life when she became part of a group called “the Kingdom of Matthias” that some describe as a cult. Initially Isabella had been drawn into a commune where she was allowed to preach and where everyone, Black and White, ate at the same table. Once the group had a different leader and became the Kingdom of Matthias, however, Isabella was no longer permitted to preach or even pray aloud when men were present. Eventually she ended up suing another former member of the cult and won. Because the victory did not give her financial independence, she returned to domestic work. Her son Peter became a sailor, and she never saw him again.

On Pentecost Sunday of 1843, Isabella felt called by the Holy Spirit to leave domestic work so she could travel while lecturing and preaching. This was when she took on the name Sojourner Truth. Koester explains: “Black people often took new names after escaping from slavery. Not only did this make it harder for slave catchers to trace them; it was also a way to shape their new identity as free people.” There was also theological significance to Isabella’s choice of a new name:

Sojourner’s new name echoed the Scriptures. The “strangers and sojourners” of Bible times (1 Pet. 2:11) were wanderers and exiles seeking a better country (Heb. 11:16). . . . When she was enslaved, her last name declared which white person legally owned her. By taking Truth as her last name, she declared herself to be a child of God.

Truth preached a message based on love, not fear, and became involved in social reform movements such as abolition, temperance, and women’s rights. She preached to White and Black audiences. She often used the story of Queen Esther to advocate for women’s rights.

Unable to read, she relied on others to read the Bible to her. She preferred children, because adult readers often interpreted what passages meant. Unashamed of her inability to read and write, Truth said, “I don’t read such small stuff as letters. I read men and nations. I can see through a millstone, though I can’t see through a spelling book.” Her Narrative of Sojourner Truth was written in collaboration with White abolitionist Olive Gilbert. Gilbert saw the book as combating slavery, whereas Truth understood it as charting a spiritual journey. While Gilbert certainly left her fingerprints on the book, she was also respectful. She didn’t seek any profits, nor did she put Truth’s speech into dialect.

Truth visited Harriet Beecher Stowe at one point, seeking an endorsement for her book, which Stowe gave. Later, however, believing Truth to be deceased, Stowe wrote a tribute to her for the Atlantic Monthly, giving Truth a plantation dialect. Stowe claimed that Truth called everyone “honey” and said that she came from Africa. Truth tried to correct the errors in the article, but the only error the Atlantic corrected was the report of her death. Years later, at a meeting of a women’s rights association, Truth asked journalists not to report her speech in a dialect that wasn’t hers.

When Truth visited Abraham Lincoln, he signed her autograph book to “Aunty Sojourner Truth,” rankling many. Truth claimed that the term aunty did not offend her; rather, she was impressed that he signed her book with “the same hand that signed the death-warrant of slavery.” She was heavily involved in trying to find homes for formerly enslaved people who came to Washington from the South following the Civil War.

Koester places Truth’s faith at the center of her activism, and there is much in Truth’s social reform that can speak to churches today. For example, Truth was disgusted by churches she visited in New York City that were only a third full one day a week while so many people endured appalling living conditions. She advocated for allowing poorly housed people into the churches and blamed the male clergy for not permitting this to happen. She believed that letting women speak and preach would help change such injustices.

As many Americans continue to awaken to the sin of White privilege, progressive Christians will benefit from reading about Truth in the context of her faith, theology, and ministry. As Koester puts it, “until everyone has their rights, there should never be a last biography about Sojourner Truth.”