Tracy K. Smith’s lovely, unflinching poems

Smith is acutely aware of injustice and violence—and remarkably hopeful about the possibility of reconciliation.

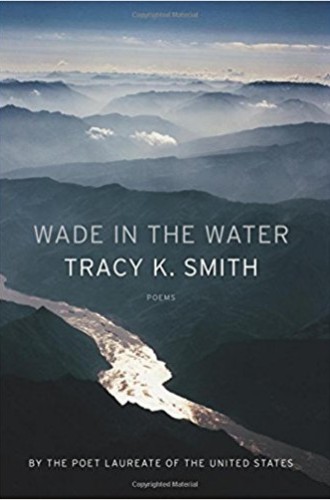

In “Wade in the Water,” the title poem of Tracy K. Smith’s new poetry collection, the poet encounters the Geechee Gullah Ring Shouters:

One of the women greeted me.

I love you, she said. She didn’t

Know me, but I believed her . . . .

The Shouters preserve, in song and dance, aspects of the religious and cultural heritage of African American slavery. Horrors are juxtaposed with love:

O Woods—O Dogs—

O Tree—O Gun—O Girl, run—

O Miraculous Many Gone—

O Lord—O Lord—O Lord—

Is this love the trouble you promised?

Smith is an exceedingly accomplished writer and poet. Her previous poetry collection, Life on Mars, won the Pulitzer Prize in 2012. Her memoir, Ordinary Light, was a finalist for the 2015 National Book Award. She was appointed as poet laureate of the United States in 2017 and teaches creative writing at Princeton.

Smith’s poems display an acute consciousness of injustice and violence. “Declaration” is an erasure poem, composed by editing out portions of a preexisting text—in this case, the Declaration of Independence. Smith is African American, and the result is telling: “Our repeated / Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury.” The poem makes its point by means of the poet’s eraser: scrape away at the surface of American pretensions, and you reveal a deeper and much grimmer reality.

“Mr abarham lincon.” So begins the long poem, “I Will Tell You the Truth about This, I Will Tell You All about It.” The poem is composed of actual (though abridged) letters and statements of African Americans who served in the Civil War and of their wives and other family members. The effect can be devastating:

I wont to knw sir if you please

whether I can have my son relest

from the arme he is all the subport

I have now his father is Dead

and his brother . . . .

In 2014, Smith wrote a short essay about poetry for the New York Times, in which she describes one of the things poetry can do. “A poem,” she says, “can examine the vulnerability at the core of the human experience.” There are poems in this collection that do just that. “In Your Condition” conveys the experience of a pregnancy, “4 1/2” and “Dusk” speak about being a mother to a child, and “Urban Youth” presents a touching memory of the poet’s own childhood.

As might be expected of a poet in Smith’s very public position, the poems often speak to public concerns. Take “Political Poem,” a poem about two mowers not further identified or described. If the mower “off to the left,” the poem begins, would somehow take it into his head to wave “at the one more than a mile away / to the right”—“that wide, slow, underwater / gesture”—and if, the poem continues, the other were to answer with “his own slow one-armed dance,” then, the poem suggests, the unthinkable might happen; in this present time of deep suspicion, division, even hatred between citizens, the exchange of random waves between two individuals working at some distance from each other could set off a “flicker of joy,” an “instant of common understanding.” Against all appearances, this remarkable poem holds out the (seemingly) entirely unrealistic—but all the more stirring for that—hope of reconciliation.

Who talks like that these days? People praying, perhaps. And Smith, in her poetry. Over a century ago, Robert Frost wrote his great poem “Mowing,” which asks, in respect of the whispering sound made by the mower’s scythe, “What was it it whispered?” Just what, just how much, can a poem mean? In her New York Times piece, Smith says that “words invite possibility,” and it may be that she envisions her very contemporary poem about mowing as giving a kind of answer to Frost’s earlier poem.

If so, Smith’s “Political Poem”—and others in this collection—represents, in the context of today’s cultural and political climate, a somewhat startling affirmation of faith in the possibilities of poetry and in the human capacity to thrive. “A poet builds better than he knows,” Frost is reported to have said in an unpublished talk late in his career. Smith’s powerfully affecting and generous-hearted poems seem to proceed from an implicit trust that this may actually be the case. These lines come from “An Old Story,” the book’s final poem:

The worst in us having taken over

And broken the rest utterly down. . . .

And then our singing

Brought on a different manner of weather. . . .

We took new stock of one another.