Ted Kooser’s poetry of the Great Plains resonates across the world

The beloved American poet lifts the everyday into the realm of the transcendent.

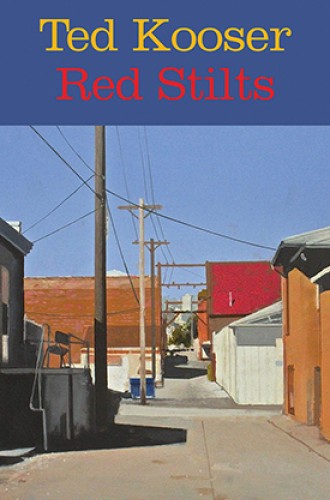

The title poem of Ted Kooser’s fifteenth book exemplifies the humility and approachability that have been hallmarks of his work for the past six decades. In “Red Stilts,” he remembers as a young boy constructing a set of stilts “from six-foot two-by-twos, with blocks / to stand on nailed a foot from the bottom.” He then describes setting out on the stilts for the first time, “not knowing how far / I’d be able to get.”

The setting of his poems has never strayed far from the Great Plains where he has always made his home, yet the poems themselves have traveled all across the world. Kooser won the Pulitzer Prize for his luminous 2004 collection, Delights and Shadows, and he served two terms as US Poet Laureate from 2004 to 2006. He also recently retired from editing the syndicated column American Life in Poetry, which now reaches 4.6 million readers worldwide each week. Kooser’s humble character, threaded throughout Red Stilts, comes as a welcome shift from the ego-driven discourse to which we have grown accustomed as a culture.

In the poem “In Early August,” Kooser faithfully renders the scene of “dragonflies, a hundred / or more out hunting together,” without needing to involve himself in the narrative. At first, he notices simply “a stirring in the golden air, the way / a glass of water stirs when some enormous truck / drives past . . .” But the poem quickly evolves beyond mere description, as Kooser allows those dragonflies to do their work in solitude: