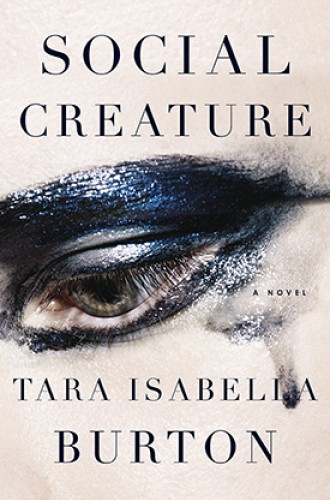

The talented Tara Isabella Burton

In Burton's debut novel, Louise and Lavinia represent the possibility that compulsive self-disclosure is a form of self-concealment.

“If personality is an unbroken series of successful gestures,” F. Scott Fitzgerald’s narrator observes of Jay Gatsby, “then there was something gorgeous about him.” In literature, if not necessarily in life, the undefined terrain between earnest self-reinvention and outright fraud is endlessly fascinating. There insecurities and aspirations mingle, class distinctions are subtly challenged and reinforced, and affectation sinks deep enough into the skin to become uncannily persuasive and almost genuine. Patricia Highsmith, in The Talented Mr. Ripley, turned Fitzgerald’s plot around by making her Gatsby figure the killer instead of the corpse. Tom Ripley not only kills the louche son of wealth who takes him on as a retainer, but adopts his identity, gets away with his crime, and makes the audience complicit in the whole performance.

Louise Wilson, the protagonist of Tara Isabella Burton’s caustic and compulsively readable debut novel, follows in these dangerous and charismatic literary footsteps. A Ripleyesque survivor in a setting where anxiety, depression, and bulimia are social and professional adaptations, Louise convinces herself that “we cannot be known and loved at the same time.” One of thousands of subsistence producers in the knowledge economy, she juggles dead-end jobs at a bar, tutoring high school students, and writing content for a bottom-feeding e-commerce site. At the age of 29, eight grueling years after arriving in Brooklyn, she is an aspiring writer who has stopped aspiring. Forcing her smiles, dying her hair, feigning a prep-school pedigree, and embracing the desires of lousy Tinder app boyfriends, Louise grimly and repetitively performs her life until she meets Lavinia Williams.

Lavinia, who hires (but never pays) Louise to tutor her devout and studious younger sister for the SAT, appears to have much more than Louise can pretend to have. She is years younger and shades blonder, adored by a patrician ex-boyfriend, and well-ensconced in the literary circles Louise has given up hope of joining. Lavinia enjoys wealth and leisure on a scale that Louise can scarcely imagine, let alone associate with on equal terms. When Lavinia impulsively takes on the blank and adaptable Louise as a friend-cum-retainer, their lives become quickly and deeply entangled.