Take & read: New books in American religious history

An ever-renewing narrative of community formed by difference

The books that have most caught my eye this year track a wide-ranging and multivalent landscape and focus on groups that have not been prominent in the received narratives of U.S. religious history—the great mythic mash-up that imagines pious but bighearted Pilgrims founding a Christian nation that nevertheless separated church from state and promoted religious freedom. That version of the story is neither good history nor a usable compass for contemporary times. These books build cultural competence by contributing to an ever-renewing narrative of U.S. religious history that views community as constituted by difference.

April E. Holm’s exhaustive research into antebellum evangelicals in Delaware, Maryland, western Virginia, Kentucky, and Missouri has produced A Kingdom Divided: Evangelicals, Loyalty, and Sectionalism in the Civil War Era (Louisiana State University Press). The book tracks the transformation of a political argument into a theological one, and it’s one that seems custom-made for the times we live in.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Holm recounts how the future mainline Protestant churches—Presbyterians, Methodists, and Baptists—divided the slaveholding South from the antislavery North in the decades leading up to Fort Sumter. But then she digs for the reason that, against expectations, those ruptures persisted after Lee’s surrender.

“Religious reconstruction” failed, Holm argues, because southern white Protestants resisted northern missionaries and federal pressures (including loyalty oaths and requirements to display the U.S. flag inside churches). Border-state moderates also resisted these pressures, eventually throwing in their organizational lot with the vanquished South, whose denominations benefited from the numbers and resources that border churches brought their way. Southern Protestantism thereby became less geographically circumscribed, while its style of Christianity—suspicious of both federal power and the black citizenry in its midst—spread more broadly. Southern-style suspicions hardened into a theological commitment to the “spirituality of the church,” which became a major bulwark against racial integration during the civil rights movement. This story matters urgently to contemporary American self-understanding.

Holm’s book may be read as a genealogy of white Christian conservatism, styles of which survive to this day. In a similar genealogical vein, Matthew J. Cressler’s Authentically Black and Truly Catholic: The Rise of Black Catholicism in the Great Migration (New York University Press) examines stories of black migrants from the South who found community in Southside Chicago’s Catholic parishes. They became Catholics, and then after Vatican II, many became black Catholics as they further reshaped an already Americanized tradition by infusing it with self-consciously African and African American impulses.

Cressler’s work adds two new dimensions to histories of religion in the civil rights movement. He shows how ritual practice contributed to black migrants’ Catholic transformation and self-understanding, and then he demonstrates how that consciousness fused Black Power with black Catholicism in a rejection of liberal interracialist Catholicism. Cressler’s black Catholics “rejected the notion that there was only one way to be Black and religious.” Not all black folk in Chicago were Protestant; not all Catholics were white. As the second-largest black Catholic community in the United States, Chicago’s black Catholics helped transform the nation and the Catholic Church with politically engaged faith during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

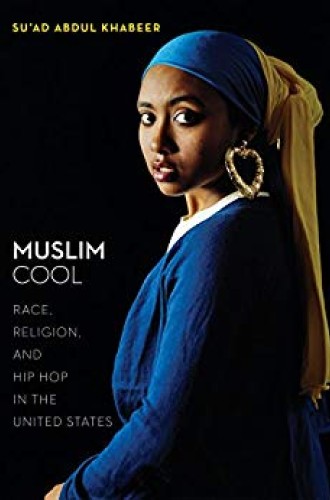

Just as Cressler’s history augments received understandings of black Catholicism, black radicalism, and civil rights, Su’ad Abdul Khabeer’s new book adds to the sometimes contentious conversations about being Muslim American. (Her research also happens to focus on the Chicago area.) Muslim Cool: Race, Religion, and Hip Hop in the United States (New York University Press) playfully welcomes prospective readers with a striking cover image: a photograph by Awol Erizku that re-creates Vermeer’s painting Girl with a Pearl Earring. The model, a woman of color, sports a modified ’hoodjab—a version of the traditional hijab worn by some Muslim women that is inflected with what Khabeer calls “the coolness of Blackness and ’hoodness.” Instead of Vermeer’s pearl, the woman wears a heart-shaped door-knocker earring, an accessory with roots in classic hip-hop.

Khabeer’s study explores how young African American Muslim women and men who embrace Muslim cool use hip-hop styles of dress, music, dance, and spoken-word performance to assert their Muslim bona fides. In so doing, they are arguing against the antiblack biases of the dominant Middle Eastern and South Asian immigrant Muslim community in the United States. But they’re also arguing for their sense of belonging in the American national community that is normed as white even as it claims to be postracial and multicultural. “Muslim Cool,” Khabeer explains, “is a move toward Blackness in the construction of a U.S.-based Muslim identity.”

The 13 highly readable chapters collected in Devotions and Desires: Histories of Sexuality and Religion in the Twentieth-Century United States, edited by Gillian Frank, Bethany Moreton, and Heather R. White (University of North Carolina Press), allow readers to explore how a variety of traditions encountered the erotics (and sometimes the sexual politics) of religious devotion in the century just ended. Readers will discover the Catholic Church’s wrestling over the distinction between sex education and obscene literature, the pre–Roe v. Wade support among white Protestants for oral contraception as a way of promoting “responsible parenthood,” Conservative Jewish women’s enduring support for women’s reproductive freedom and abortion care; Mormon women finding political power in traditional female roles and opposing the Equal Rights Amendment; and varieties of gay and lesbian Jews and Christians leading established communities and shaping new ones. The connections between sex and religion are much misunderstood and misused in contemporary debates, if even acknowledged. This collection sheds new light on a rich and mutable relationship between human and heavenly desires.

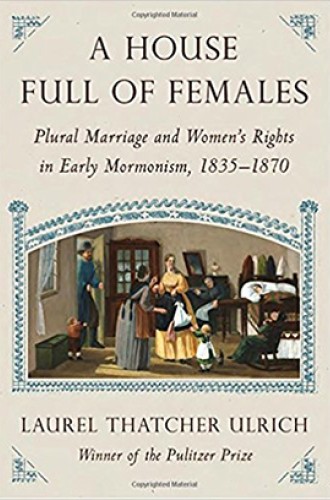

The latest book from Harvard historian and Pulitzer Prize–winner Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women’s Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835–1870 (Knopf), regards Mormon women’s struggle to defend their community’s religious freedom and to gain their own suffrage as the connective thread of the American-born patriarchal tradition. In so doing, Ulrich presents readers with a powerful example of feminist consciousness that did not begin among an eastern elite.

The book is grounded in 19 first-generation Mormon figures’ writings: diaries, letters, memory albums, and society writings. They report surprisingly egalitarian wedding vows, women as well as men healing and speaking in tongues, and women providing for families and caring for itinerants while husbands served missions. These early Mormon women displayed their full humanity in disagreeing, sometimes boisterously, with each other and with their husbands, brothers, religious leaders, and even representatives of the U.S. government. They deliberated and disagreed about the plural marriage system, weighing its promises against its demands. Some of them embraced the former, while others focused on the latter and resisted, although usually deciding to stay in the fold. Ulrich shows not only how plural marriage could foment solidarity among sister wives but also how the presence of women’s sustaining religious activity—a signal characteristic of American religious communities past and present—aligns Mormonism with more familiar religious communities in the United States.

Reading between the lines, one might discern an argument for female priesthood or at least for a reinvigoration of the church’s Relief Society along first-generation lines. In any event, Ulrich’s narrative deepens the American religious story with its empathetic, human story of Mormon women and men living out their faith during a key period of American history. As physical boundaries and cultural ideologies about gender, race, and religious belief settled into place, these Mormons claimed to be both authentically Christian and truly American.

Attending to the submerged parts of American religious history reveals how connections among religious belief, sexuality, violence, and liberation have, for good or ill, had an impact from colonial times to the digital age. As we gain broader understanding of how religious folk lived their pasts, we acquire deeper sensitivity to similar commitments circulating in the present.