Take & read: Global Christianity

New books that are shaping discussions about global Christianity

Christianity is growing worldwide, and the reasons for that change are vigorously debated. In simplest form, the disagreement is about how much political power determines the shape of faith. Beyond mere submission to power, what induces people to live—and die—in faith?

That question is the subject of substantial recent literature on the early modern world, including the Iberian-led expansion of Catholicism between about 1500 and 1700. Undoubtedly, Spanish and Portuguese conquerors and traders demanded submission to the church. But what did those new converts actually do with the Christianity they received? What options did they have? Karin Vélez offers some important answers to these questions in her mind-stretching study The Miraculous Flying House of Loreto: Spreading Catholicism in the Early Modern World (Princeton University Press).

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The House of Loreto was reputedly the original home of the Holy Family, which was miraculously transported to Italy after the Muslim conquest of Palestine in 1291. As Catholic empires spread worldwide they took with them devotion to the House of Loreto. Vélez studies three 17th-century shrines in the New World: one among the Huron in Québec, another in the Amazon River basin between today’s countries of Bolivia and Peru, and a third on a peninsula in Baja California. Throughout, Vélez finds that local native people were overwhelmingly responsible for supporting and fostering the shrines through “vast and voluntary participation, . . . real, repeated self-enlistment.” While the Iberians imported the cults, native people appropriated them wholeheartedly.

Vélez is to be congratulated for taking lived religion seriously and just not describing the attitudes of literate elites. Provocatively, she compares the Catholicism of that era to Wikipedia: both are “additive,” based wholly on grassroots participation and enthusiasm, “not just trained or credentialed authorities sitting far away in some elite metropolitan center.”

Questions about how deeply local manifestations of faith are shaped by global forces also arise in the study of modern evangelicalism. Melani McAlister’s fine and substantial book The Kingdom of God Has No Borders: A Global History of American Evangelicals (Oxford University Press) concentrates on the American role in global evangelicalism. To what extent were (and are) American evangelicals, consciously or otherwise, presenting an American gospel globally?

McAlister shows how American believers were influenced by overseas (particularly European and British) thinkers and analyzes how that influence affected the messages they brought to the Global South. She also demonstrates the richness of a dynamic interplay between North and South as Southern churches accepted the gospel offered but promptly and comprehensively adapted it to their own needs. Given the controversial nature of so many of the resulting disagreements, especially in areas of gender and sexuality, McAlister is commendably fair in her approach. This evenhandedness may come from the author’s firsthand experience in mission settings, including in the Sudan.

Sudan also sets the scene for an excellent study of how local people receive Christianity and make it their own: Jesse A. Zink’s Christianity and Catastrophe in South Sudan: Civil War, Migration, and the Rise of Dinka Anglicanism (Baylor University Press, Studies in World Christianity). The basic story is straightforward, if sometimes horrible in its details. During the late 20th century, Christianity spread rapidly among the black African people of southern Sudan, who lived under the oppressive rule of Arab and Muslim elites in the north. Wars and guerrilla struggles persisted until the new nation of South Sudan came into existence in 2011, and civil strife continued thereafter. But Zink’s study goes far beyond the politics. He shows how a seed planted by the Anglican Church Missionary Society blossomed and flowered through the passionate and self-sacrificing work of thousands of Dinka people, usually women or young men, the very people who had little say in traditional social structures.

Repeatedly, we see the Dinka accepting the faith, and specifically in its Anglican form, because it met their social, cultural, and spiritual needs. The burgeoning Anglican Church fulfilled many essential functions that in a more economically advanced society would assuredly fall to government, especially given the persistent refugee crises in the area. Readers of Vélez will immediately recognize the ways the Dinka appropriated the faith and incorporated into it essential aspects of their older beliefs.

Zink has given us an exemplary study of Christian faith in a Global South context. The problem that readers face is the sheer proliferation of local studies and microhistories. In that context, a new series from Fortress Press supplies an essential navigational guide to the global picture. Understanding World Christianity includes highly accessible volumes surveying (among other regions) India (Dyron B. Daughrity and Jesudas M. Athyal), Eastern Africa (Paul Kollman and Cynthia Toms Smedley), and Mexico (Todd Hartch).

The latest contribution to the series is Kim-kwong Chan’s Understanding World Christianity: China (Fortress). The value of this concise and well-balanced survey, based on four decades of firsthand observation, will be instantly apparent to those daunted by the ever-growing range of specialized academic volumes on diverse movements and regions. Although the precise number of Chinese believers is much debated, there is no doubt that the country’s churches will be among the world’s largest in coming decades, and the political and religious dilemmas they face demand our attention. There is no better place to start than Chan’s tour de force.

Each volume in the series uses a common structure of chapters divided under the headings of “Chronological,” “Sociopolitical,” “Denominational,” “Geographical,” “Biographical,” and “Theological.” That may sound overly rigid, but it works well in organizing potentially unruly material. In Chan’s volume, the biographical section is a particular treasure. Chan offers moving case studies of Christian individuals. It is clear that their faith is utterly, quintessentially Chinese and very far removed from any foreign or imperialist origins. Like the Dinka, and like the indigenous faithful described by Vélez, these Christians believe that their faith made a direct journey from Jerusalem to their doorstep without any intervening stops.

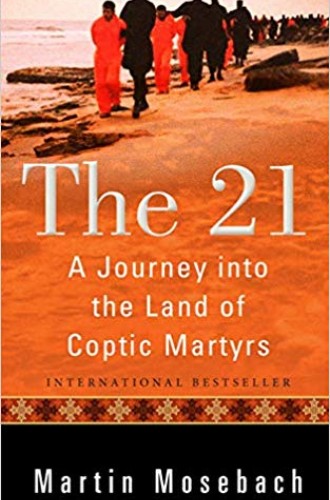

Turning to a church that did receive its faith directly from Jerusalem many centuries ago: in February 2015, ISIL terrorists murdered 21 construction workers in Libya who were Christian, all but one of them from Egypt’s ancient but vigorous Coptic church. These simple men all died affirming their faith, and all were promptly recognized and venerated as martyrs. Fascinated by the zeal that ordinary Coptic Christians showed for their spiritual warriors, journalist Martin Mosebach set off to investigate their religious world. The 21: A Journey into the Land of Coptic Martyrs (Plough) portrays a world defined at every stage by faith and loyalty to the church. Incredibly, that situation endures after a period of almost 1,400 years during which the Coptic church has existed under the power of Islamic authority, when Christian faith stood no chance of winning worldly rewards. Read alongside the stories of new and emerging churches, Mosebach’s book raises challenging questions for people in more prosperous Christian lands where faith is fading.