The suffering Jesus in Shawn Copeland’s theology

African American spirituality and God’s act of solidarity

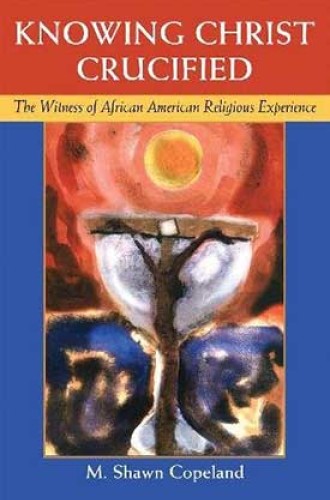

The cross is a book, St. Francis of Assisi reportedly said. In seven provocative, incisive essays, M. Shawn Copeland “reads” the book of the cross across centuries of African American experience and culture. This is not a systematic treatise, but together these pieces sketch a bold constructive theology that integrates black liberationist commitments with contemporary critical theory, Roman Catholic spirituality, and post-Vatican II thought. Copeland retrieves and reenvisions Christology within a “practical-political theology” that names and directly confronts social suffering—especially that which has been spawned by white supremacy, slavery, segregation, and ongoing racial injustice. Though this is an erudite work of academic theology, ideal for use in seminary or college classrooms, pastors, lay people, and activists also will profit from it.

Copeland discerns a cruciform shape in African American slave narratives; she begins with the inception of race-based chattel slavery in the colonial Americas and ends with the hate crime and mass murder in Charleston and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. She explores the “dark wisdom” in these narratives, forged by a people ripped out of their ancestral lands, stripped of their cultural and religious traditions, rent from their family members at auction blocks, beaten, sexually abused, and terrorized; but she also uncovers a fervent and persistent faith in the God who raised the crucified Jewish Messiah from the dead. Echoing the political theologian Johann Metz, Copeland reckons these narratives as “dangerous memories, memories that challenge” us even today, as we seek to embrace a discipleship marked by cruciform praxis in solidarity with the dispossessed.

A striking biblical spirituality permeates these stories. Slaves typically were forbidden to congregate, worship, sing, and drum together. Still, in fleeting hours of leisure or in the dark of night, slaves would steal away into the woods to pray, an act of resistance. Copeland recounts the story of “Praying Jacob,” a devout Maryland slave who defiantly asserted—even when held at gunpoint!—his right to halt his tasks three times a day for prayer. “Praying Jacob disarmed slavery’s power over his body through committed Christian discipleship. Death had no power over him; he was a follower of Jesus of Nazareth in word and deed,” she writes.