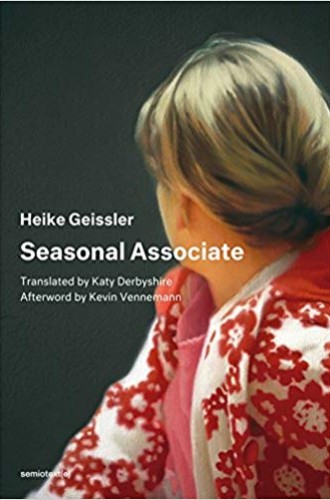

A story that puts you in an Amazon warehouse worker’s shoes

Heike Geissler’s account of her time at Amazon is far more than a workplace exposé.

In 2010, when her freelance writing and translating gigs weren’t producing enough income to pay the bills, German novelist Heike Geissler took a seasonal job at the Amazon distribution warehouse in Leipzig. There she spent her days (and sometimes nights) unpacking items from boxes, inspecting them for damage, scanning them into the computer system, and placing them in a crate that the managers insisted she call a tote—a homonym for the German word for death. The work was boring, physically demanding, and demoralizing.

Geissler’s account of her time at Amazon is more than a workplace exposé. Hovering somewhere between memoir, cultural criticism, and fiction, it’s a compelling meditation on the psychological and physical harm of working for a large corporation in a society driven by neoliberal economic goals. In the middle of an argument with a coworker about the right way to stack boxes and crates, the narrator comes to a sober realization:

You’re like a coal miner who wants to split a rock with a big heavy hammer, who raises a hammer he can hardly lift, and brings the hammer down on the rock with full force, but can’t make even the tiniest chink. You hope for fast results, where only continuous light work is possible and necessary on that rock.