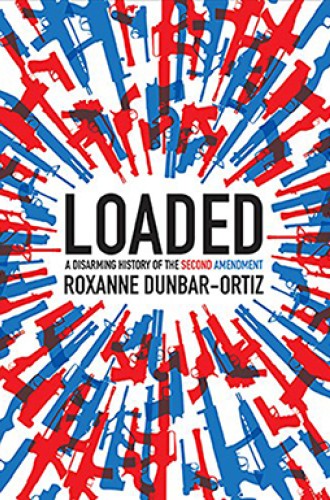

The Second Amendment is racist at its root

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz's social history highlights who's at the other end of the barrel.

The Second Amendment consists of a single, 27-word sentence: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” Embedded within it is a grammatical ambiguity that, two and a quarter centuries later, divides liberals and conservatives on ideological grounds: How is “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms” connected to “a well regulated Militia”?

If, as liberals argue, the original meaning of the Second Amendment was to ensure that each state could form a militia, then Congress (and now, by extension, the states themselves) may regulate firearms on an individual basis as long as “the people,” collectively, can form a state militia. If, as conservatives argue, the reference to militias is merely prefatory, the original meaning of the Second Amendment grants individuals the right to keep and bear arms, thus restricting the government’s ability to ban an individual’s ownership of firearms. This debate over the Second Amendment has been litigated to the United States Supreme Court and continues to frame the debate surrounding even moderate gun control measures.

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, an indigenous rights activist and historian, argues that the Second Amendment indeed “enshrined an individual right”—and did so to allow settlers to “form volunteer militias to attack Indians and take their land.” In interpreting the Second Amendment’s legal effect narrowly, she argues, liberals “delude themselves” and “fail to comprehend the history embedded in U.S. culture and social relations.” To underscore her interpretation of the Second Amendment’s original purpose, she looks to how the colonies permitted—and, in some cases, required—gun ownership as essential to settlers’ survival. Virginia, for example, enacted a slew of gun ownership laws during the 17th century, including one that required men to travel with firearms when attending church.