Ruth Bell Graham’s adjustments

Anne Blue Wills highlights the complexity of a woman convinced by her Christian culture that she was created by God to support her husband.

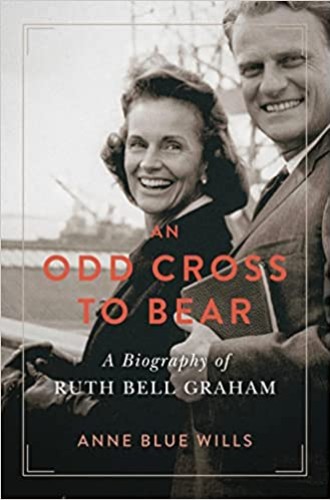

“An odd cross to bear” is an odd but apt phrase that Ruth Bell Graham used to describe her life. Historian Anne Blue Wills effectively argues this point in her biography of Billy Graham’s spouse, which draws on Ruth’s published writings and “observers’ accounts.” While additional material by Ruth’s own hand would lend a more complete portrait, the letters and diaries remain in possession of the Graham family and have not been made available to the public. Despite this limitation in source material, Wills provides a clear lens through which to see the chronology of Ruth’s life and offers key contextual clues, especially related to race and gender.

In a well-paced narrative, Wills traces Ruth’s Presbyterian missionary childhood in China, where she saw the 19th-century idea of Western women evangelizing Asian women up close and embraced this experience as one she would likely emulate. Her formal education mirrored that of other missionary children who were sent to boarding schools. For Ruth, this meant going to Pyeng Yang Foreign School in Korea, where she was “desperately homesick.” Later, Ruth traveled to the United States to study at Wheaton College, at which point she believed her future was determined. “I would never marry,” she wrote. “I would spend the rest of my life as a missionary in Tibet.”

Instead, Ruth met Bill Graham and, after a period of questioning her missionary calling, accepted his marriage proposal. In her journal, she wrote, “Somehow I need Bill. I don’t know what I’d do if, for some reason, he should suddenly go out of my life.” While Bill traveled extensively throughout most of their marriage, Ruth reared five children and maintained their homes, including purchasing land and overseeing building construction.