The relational religion of Martin Buber

Behind the man’s life’s work is a broken-hearted child.

Following a fall college semester abroad in Jerusalem, with instruction from Jewish, Muslim, and Christian teachers, I spent the January term reading Martin Buber’s works in English translation: Tales of the Hasidim, The Legend of the Baal-Shem, Between Man and Man, and others. Buber seemed to be carrying readers toward the soft, living, hidden heart of Jewish faith and tradition. His poetic, mystical writing seemed to welcome readers of all faiths, or none, to relational religion and into the spiritually beneficial exercises of puzzlement, meditation, and clarifying conversation.

Nearly 40 years after my college-age introduction to Buber, my son, an engineering student at a Massachusetts university, took a class on the concept of love. The professor assigned I and Thou, and my son, in a degree program quite different from my own, enjoyed parsing and pondering I and Thou.

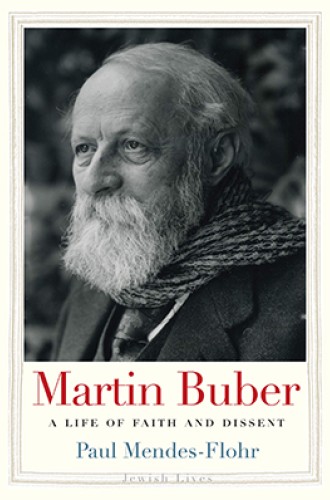

Behind Buber’s life’s work, which at its core still seems aimed at young people, is a brokenhearted child. His parents separated when he was three, and his mother left him without saying goodbye. Paul Mendes-Flohr describes the child looking out from a second-floor window at the figure of his mother walking away, without a wave, to elope with a Russian military officer.