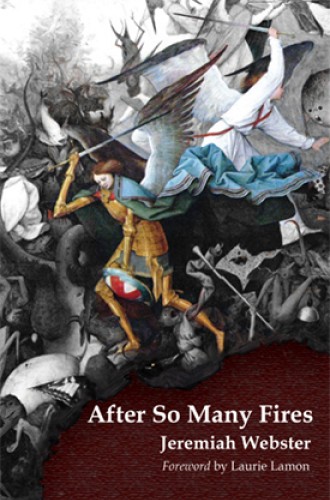

“The world falls apart.” So, in an echo of W. B. Yeats, says the refrain of the first poem in Jeremiah Webster’s ambitious and much affecting debut poetry collection. Webster teaches English at Northwest University in Washington State and has published anthologies of T. S. Eliot’s and Yeats’s poems.

His collection opens with “Credo,” a poem designated as prelude to the book. Over the course of 20 lines, the phrase “the world falls apart” appears eight times. This, the poem seems to insist, is the main thing to be said about the world in our time and place; it is the principal reality behind our lives and our deaths, behind the work we do. “I build my home,” the poem declares, “as the world falls apart.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

It’s this reality that serves as backdrop for most of the poems to follow. There is, for example, the human degradation of the environment and the willfulness with which we carry it out. “Ecclesiastes” alludes to the helplessness of barndoor skates, pelicans, and sharks in the face of predatory human greed and seems (in its final stanza) to affirm that this is nothing new under the sun:

Here is St. Peter,

Vitus Bering’s sea vessel of 1741.

The first mate admires

how suitable the fusiform body is for the sea

before slaughtering the last sea cow.

The poems “AP Story: Bear Recovering After Reconstructive Surgery” and “AP Story: Cloned Mules Lose to Naturals in Pro Race” provide seriocomic examples of human arrogance toward animals—and, by implication, toward all of nature.

Our world’s excesses of technology and violence also come in for their share of unfavorable notice. In “Letter to my Grandson (Who is probably a Cyborg),” the letter writer is on the attack: “They tell me all identity is algorithm, / . . . that your mind has no use for the technology / of books I saved for you on shelves.” And, in “New Normal,” violence and its media coverage are just part of the daily routine: “Redundant terrorism / arrives with the coffee.”

Like Eliot, Webster is an instinctively religious poet in the sense that his poems strive to see into a reality much deeper than our senses can perceive. In a further similarity to Eliot, what Webster points to as the way forward may actually look and feel like going back. Recall Eliot in “Little Gidding”: “And the end of all our exploring / Will be to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.” Webster’s poems seem to counsel a return to God, but without illusions that it will occur on a wide scale at any foreseeable future time.

Having forgotten about God, Webster’s poems seem to be saying, we have placed false hopes in our own mastery in the form of ever-advancing technology. Our first task must therefore be the difficult and humbling one of giving up what hopes we have—of accepting our present desolation, in order (one might almost say) to discover what Christianity calls the “negative way” back to God.

According to the poem “Surveillance”: “The camera . . . / resides in the private / space that once belonged / to a lover, liturgy, / omniscience, / a god.” In another poem, “For our own good,” the poet asks:

Can I continue to believe

in the neutral gaze of technology

as algorithms assign guilt

and avatars eavesdrop?

And then he gives a kind of answer: “No database forgives / as the abandoned God once did.”

“Dissonance” is among the most fully realized and resonant of the poems in this collection. It begins with a gift to the poet of an old, worn-out piano that has to go to the dump. For the poet, in his disappointment, the piano becomes a stand-in for the world’s defaced beauty. He responds: “Can the violent receive such impotence . . . / that I might take solace / in an equality of broken things . . . ?” So much for hope, the poet seems to say, in the things of this world.

So what are we to do? Webster concludes his collection with a long and luminous poem titled “Ilium,” which serves as postlude to the book and which would warrant an essay of its own. For now, it is enough to say that this concluding poem can be read as an extended fleshing out of an assertion contained in the earlier poem “Ritual”: “To wait without hope / is not the same as despair.” The world of “Ilium” is recognizably our world—the world we inhabit from day to day—and is indeed falling apart. It is a “vast diversity of loneliness”; a world whose inhabitants spend inordinate hours slouched over smartphones, “the private miracle: the incarnate screen”; where “nature lies prostrate before . . . [the people’s] electric defiance.” And yet, “Ilium” also speaks of children and forgiveness and singing. It ends with these lines:

And though each generation

carries the promise of apocalypselet us sing hymns

saints cannot teach,stoke fire from fallen branches

a little while longer.