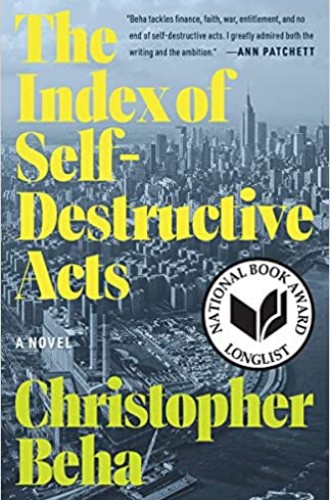

A novel about baseball, wealth, and human frailty

Christopher Beha’s characters find themselves in pits, and the way out is not remotely clear.

The index of self-destructive acts is a little-known baseball statistic that tracks how frequently a pitcher does something stupid—balking, pitching wildly, hitting the batter—through no one’s fault but his own.

But in Christopher Beha’s novel, the index is a metaphor for human frailty, striving, and failure. “It’s worse than a crime,” the antihero Sam Waxworth says at one point in an act of desperate self-preservation that is also self-destruction. “It’s a blunder.”

The novel centers on a New York City family, the Doyles. Frank Doyle is a famous columnist for a newspaper that most of the characters read obsessively. His notoriety comes from his cantankerous takes on politics and baseball, but when the novel opens he has just doomed his career by making an on-air racist joke about Barack Obama. He’s lost his job and pretends to be writing a book but instead watches baseball highlights on repeat.