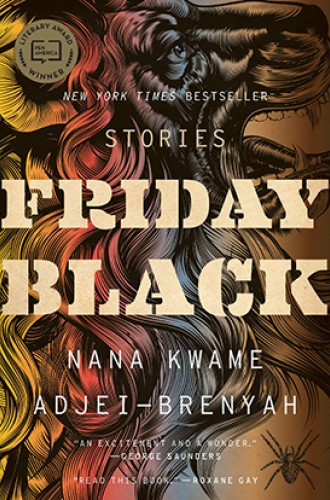

Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah’s short stories reveal the insanity and violence of our society

Evoking the murders of unarmed black men, this collection is meant to appall us.

In “The Fiction Writer and His Country,” Flannery O’Connor famously explained her method for writing short stories: “for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures; to the hard of hearing you shout.”

Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah is a new writer with a striking ability to do as O’Connor suggests. Many of the stories are exaggerated, overdrawn to the point of being bold and strange. Because of the way they play with caricature, you can argue with them and say, “Life doesn’t really look like that. People don’t act that way.” And then you recognize that the larger-than-life nature of the story has been drawn for your benefit. You are the hard of hearing; you are the almost blind.

The opening story, “The Finkelstein 5,” begins on an ordinary morning when the narrator, Emmanuel, is getting dressed for a job interview and has to decide how black he wants to appear. This isn’t a question of skin color, he tells us, because his skin is a “deep, constant brown.” It has to do with subtler things: clothing choices, how he chooses to walk or wear his baseball cap, his speech. On the phone, he can get his blackness down to a 1.5 on a 10-point scale. But in person, he can never go lower than a 4.0, no matter what he does.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

These choices shape many aspects of Emmanuel’s life, including job opportunities, how people treat him in public, and his personal safety. The blacker he appears on the scale, the more afraid of him white people are—and the less safe he is in the world.

The story is haunted by its backstory: the murder of five black children by a white man who has claimed self-defense. Emmanuel ruminates over these murders, responds to them, and interacts with the memory of them throughout the story. “The Finkelstein 5” shows how race, in our society, is a language. It’s a visual and psychological vocabulary that we have tied intricately to who is safe from violence and who is not.

Adjei-Brenyah is at his best when revealing these violence-tinged aspects of contemporary society. He exaggerates something that we all take for granted until we can see it for the insanity that it is. The title story, “Friday Black,” does this for the consumer-culture ritual Black Friday. “It’s my fourth Black Friday,” the narrator, who works for a coat retailer in a mall, says. “On my first, a man from Con necticut bit a hole in my tricep.” As the story unfolds, greed and ambition turn into absurd violence.

“The Era” carries multiple layers of satire but seems to be aimed most directly at a society that wants to manufacture rather than raise children. Most of the children in the adolescent narrator’s school have been selected through a service called OptiLife™. After their births, their behavior is managed through various concoctions of drugs. Another story, “Through the Flash,” takes its characters through cycle after cycle of mindnumbing violence, as if to point to our own shoulder-shrugging acceptance of it.

Adjei-Brenyah evokes the murders of unarmed black men throughout the collection, and one story, “Zimmer Land,” is a direct exploration of the death of Trayvon Martin. This story joins “The Finkelstein 5” among the collection’s most troubling stories. Zimmer Land is a theme park where white people pay money to pretend to kill black people. The main character voluntarily plays one of the black men ritually killed. He hopes that by doing so, he can minimize violence done in real life to black men.

“Zimmer Land” puts its finger exactly on the law-and-order fiction, dehumanization, and self-justification that lie behind much white-on-black racial violence. The moral dilemma of the main character cuts deeply.

These stories owe an obvious debt to the twisted fictions of George Saunders, whom the author credits with teaching him to “laugh in the dark.” But they are less hopeful and more pointed than Saunders’s stories. If you aren’t appalled, as the saying goes, you aren’t paying attention. Adjei-Brenyah wants you to pay attention and be very appalled.