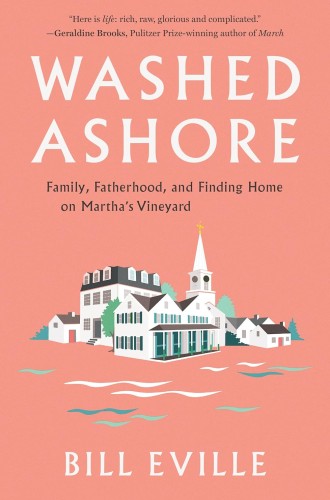

Memoir of a pastor’s husband

Washed Ashore is, at its heart, about a man growing up while raising children.

There aren’t enough books about being a pastor’s spouse, and most that come to mind are terribly old-fashioned. Here at last is a book about being a pastor’s husband. As a bonus, it’s about a stay-at-home dad who has to deal with his feelings of inadequacy. It portrays his foibles as a father and being jolted by his wife’s cancer diagnosis. And it’s set on Martha’s Vineyard, a place so enviable as to recall A Year in Provence or Under the Tuscan Sun.

Bill Eville has long harbored dreams of producing a book, and one senses that a lot of stifled ambitions have gone into this one. Twenty years ago he left the film industry, where he had helped to develop scripts, for a start-up business that he thought would let him write. The business failed. Kids came along; his wife, Cathlin, stepped in as breadwinner and served as a pastor in Manhattan. Eville took a master’s in creative writing. Then in 2008, Cathlin was called to the First Congregational Church of West Tisbury, and they exchanged one island for another.

To be “washed ashore,” in island parlance, is to be a newcomer. Although Eville’s ancestors had lived on Martha’s Vineyard, he did not have standing as an islander. Nor did he have much of a history in church. In some of the book’s best passages, he writes vividly of what it’s like to love someone who happens to be a pastor while not sharing that person’s faith.