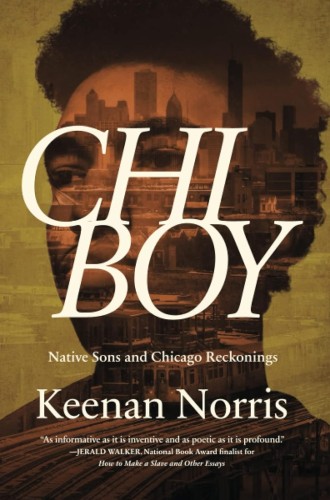

Memoir of a native son’s son

Keenan Norris’s sobering book explores Chicago’s role in forging the identity of the Black man in modern America.

Chi Boy

Native Sons and Chicago Reckonings

Chi Boy is in style and in form a pastiche, with the city of Chicago as its axis mundi. Keenan Norris presents Chicago as both the existential and the historical touchstone for the composite American that is the Black man, from Richard Wright to Jeff Fort to Barack Obama to those who died young either in the city or in deep connection with it: Emmett Till, Yummy Sandifer, and even a young Black woman, Hadiya Pendleton. Chicago in Norris’s narrative is the essence of the Great Migration in all its potential and all its tragedy, a chronology borne out in the unique political machine that was Richard Daley’s mayoralty and later in the city’s scandalously relentless murder rate.

At the same time, Chi Boy is a book written by a son about his father. Its formal arrangement as pastiche foreshadows this throughout and brings it into utter and utterly beautiful relief in the closing chapters.

There is method to Norris’s juxtaposition of pastiche with memoir: those closing chapters in which the author reconnects with his dying father would be far less forceful without the preceding, ruminative assemblage of history, social analysis, family lore, and speculation that are the circumstances of “the boy who would become the man who would become my father.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The world of Keenan Norris’s father began in Chicago and was in some meaningful sense always “Chicago.” Calvin Preston Norris was a native son of the city, a Black boy whose experience was marked by real poverty and genuine promise. What was bred by the city and what was in his bones as a human being remains a riddle. Naturally fast, Calvin became a track star whose speed would eventually result in a college scholarship. Before that, in one of this book’s most remarkable scenes, Calvin’s mother removed her son from a domestic situation made impossible by his father, heading west in the family car, only to see the man of the house she was leaving follow them and eventually, with his wife’s acquiescence, commandeer their westward journey. The scene shows how much of Calvin is encompassed by each of his parents: the admixture of defiance with determination, the insistence that a wrong can be made right. Tenacity of character—exhibited in very different ways by both the mother and father on that journey—captures both what Chicago imposes on Black people and what it elicits from them by way of response.

Ultimately, that imposition presents stark options: to leave or to die. If Norris is most interested in the story of his father, who left Chicago for Fresno, California, he is bracingly clear about the cost of staying. For Norris, it is the exemplarity of figures such as Wright and Obama that guarantees their departure from the city, while it is the fate of those like Yummy Sandifer who stay to die young. Norris finds in his father a Black man who strikes an unusual middle course: saved by a mother who removes him from the city for a life that is, if publicly unremarkable, distinctive and truthful to his self.

All of this makes Chi Boy at once sobering yet hopeful. Such is its particular force that as a longtime resident of the city’s South Side I found myself at sixes and sevens, at once nodding in agreement while objecting irritably to some of the book’s broader strokes. Such idiosyncratic sortings are ultimately beside Norris’s point: the powerful claim that Chicago is the city that more than any other has forged the fraught identity of the Black man in modern America.

Chi Boy is at its best in showing the complex vectors of this claim within the Black community itself. This emerges forcefully in Norris’s engagement with the complex dialogue within the Black community about the reflexive ways in which Chicago is represented, especially in cinema and in music, as inveterately and savagely violent. Norris’s rendition of the “Chi-Raq” controversy as it plays out among cultural actors as various as Spike Lee, Kanye West, and Chance the Rapper is subtly observed and a forceful rebuke to one-dimensional representations of this complex urban space. Debates within the Black community about how best to represent Chicago offer the most persuasive evidence to support Norris’s brief for the city’s formative significance for Black men.

A second, equally complex yet more personal vector is Norris’s emphatic and movingly rendered return, in the book’s closing chapters, to his father and their rekindled relationship as his father lives out his last years. Norris describes in spare, honorific detail his father’s immense dignity in the face of acute diagnoses that he survives against all odds, as well as the serenity of his eventual death. The book emerges, in this closing account, as the elegy of a life that exemplified serenity, wisdom, and courage even as it did not exemplify the conventional patterns of good fathering.

The last and decisive truth in Chi Boy is that the father gives the son in the way that he dies what the son most needs. And the reader in turn understands how this gift has prompted the son to retrace by any and all means available the steps his father had to take—in Chicago and beyond—to accomplish that.