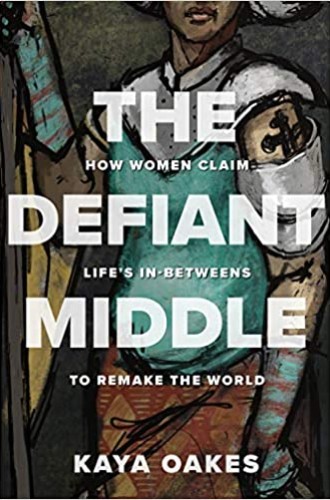

A manifesto for middle age

Kaya Oakes seeks the wisdom of women who are young, old, crazy, barren, butch, femme, angry, other, and alone

“How are your children?” asked a colleague. We hadn’t seen each other in person for a while due to the pandemic.

I stared at him. “I don’t have children,” I reminded him. “In fact, I’m writing a book about being childless.”

“Oh,” he said. “I wonder why I thought you had them.”

I’ve never met Kaya Oakes, but I immediately wanted to tell her about this conversation. It so clearly exemplifies her point about childless women being constantly outed by supposedly safe questions.

The Defiant Middle isn’t just about childless women, although that is the topic of one of my favorite chapters. In the book’s introduction, Oakes describes how she entered middle age and sought out middle-aged women in books, television, and movies. She found most of them doing one of several things: “screaming, crying, throwing her phone, frowning in a dressing room, getting divorced, getting cancer, fighting with her children, fighting with her parents, or embarrassing herself repeatedly.” Thankfully, she looked beyond these stereotypes to focus on marginalized women who defiantly engage in other activities as they move from the margins to the middle.

Oakes encourages women to think of themselves as medieval instead of middle-aged. She divides the women she studied into seven categories: young, old, crazy, barren, butch/femme/other, angry, and alone. Each chapter contains ancient and contemporary examples as well as intense, sometimes bitingly funny anecdotes and wisdom from Oakes’s life experience, including her own hysterectomy and gradual aging. “In my experience,” she writes, “physical decline is more like a car you keep driving because you can’t afford to replace it.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

While some of the women profiled in these pages include luminaries such as Joan of Arc and Mary the mother of Jesus, Oakes also includes lesser-known members of the defiant middle. She writes about Pauli Murray in her chapter “Butch/Femme/Other,” Sarah Bishop in “Alone,” and Saint Dymphna in “Crazy.”

After introducing readers to Dymphna, Oakes asks, “Why did the church fathers decide that a victim of incest would make a good patron for people struggling with anxiety, depression, and everything else on the spectrum of mental health?” She then answers her question, reflecting on the church’s discomfort with women’s sexuality and its love of women as victims. As the chapter proceeds, Oakes takes this further by demonstrating that women writers are also too often depicted as victims, offering the example of Sylvia Plath. “The problem wasn’t Plath herself or her writing,” Oakes asserts. “It was the way we were taught to talk about her, which always centered on her depression and the fact that she died by suicide.”

As a pastor, I was especially grateful for the chapter on so-called angry women. My parishioners often seem ashamed of their anger, considering it somehow unfaithful. Oakes discusses the anger of Dorothy Day, cofounder of the Catholic Worker movement and hero to many. While Day’s anger makes sense to me, I hadn’t read much about that aspect of her before. Oakes notes that Day’s “anger is often swept over in favor of focusing on her holiness.” I hope to turn to these pages again when I preach about anger, to point toward the way anger can be linked to holiness, as opposed to being an emotion that needs to be overcome.

My favorite chapter, called “Barren,” includes lines that had me laughing out loud, such as “Oh, you’re not at the toddler bacchanal either? You must also be barren. Huzzah! Pull up a chair,” as well as a reference to Mary Magdalene as the patron saint of mansplaining. Oakes lifts up inspiring examples of biblical women without children, such as Esther and Thecla.

She reminds her readers that “we need to stop defining those women by the idea of their lives as a perpetual state of absence.” (I am tempted to send this book to my colleague who asked me about my children.) Oakes further reminds us that Jesus and Paul didn’t have children either, “but the church fathers don’t dwell on that, probably figuring they were so busy that they wouldn’t have been great at diaper changing.”

In a chapter called “Alone,” Oakes points out that while we tend to romanticize male hermits, women who are attracted to a similar life have historically been regarded with suspicion. I have heard how alienating the church can be for single people, so I spent extra time on this chapter and learned that church is not the only difficult place for solitary women. They need to prepare for traveling alone and face aggressions for doing so, and even going to dinner or a movie alone can present challenges.

Oakes herself often sounds angry, but this appealed to me as a reader rather than alienating me. She closes with a “manifesto,” in which she points out how many women’s stories have been lost to history, and yet women survived. She writes about female whistleblowers and what that has cost them. She highlights the ways religious institutions have been held accountable because of women. She ends the book with questions that are meant to leave readers ruminating. And this ruminating itself, I suspect, can be the beginning of the kind of defiance Oakes calls for.