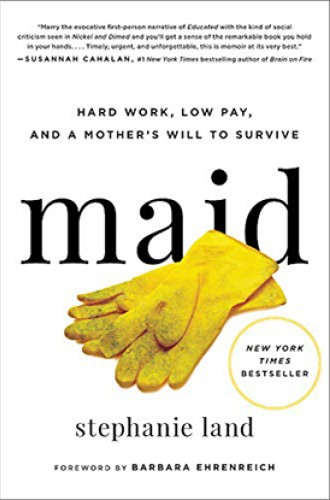

A maid bears witness

Stephanie Land's memoir reveals the intimacy and power of a housecleaner’s labor.

Stephanie Land’s memoir is a dispatch from the front line of the struggle for a living wage. It demonstrates that when your take-home pay is six dollars an hour, no math works. Rent plus groceries will always exceed income. As a young single mother who leaves a violent boyfriend, Land begins cleaning houses to support herself and her daughter: “My job offered no sick pay, no vacation days, no foreseeable increase in wage, yet through it all, still I begged to work more.”

Her description of cleaning houses is as precise as the labor is punishing. Turning the minutiae of underpaid domestic work—sponges and rags, pink mildew and dog hair, pay stubs and WIC coupons—into a gripping tale requires a particular kind of narrative talent, and Land has it. She also demonstrates a surprising empathy for those she could easily resent: her clients. When she discovers stashes of sleep aids and anxiety meds in their houses, Land muses, “Maybe the stress of keeping up a two-story house, a bad marriage, and maintaining the illusion of grandeur overwhelmed their systems in similar ways to how poverty did mine.”

Readers accustomed to the supportive network of a church may wish Land would attach herself to one. Along with her parents’ relative financial security, the “shroud of religion” gave her and her brother a sense of safety in her early years, but faith is something she has left behind. Land recalls her youth group witnessing on the street and handing out gifts at Christmas—efforts, she says, that were well-intentioned but that made “poor people into caricatures—anonymous paper angels on a tree.” Now that she’s the one who would receive a church’s works of mercy, she realizes that there is no way “to put ‘health care’ or ‘childcare’ on a list.”