A magical world of daily bread

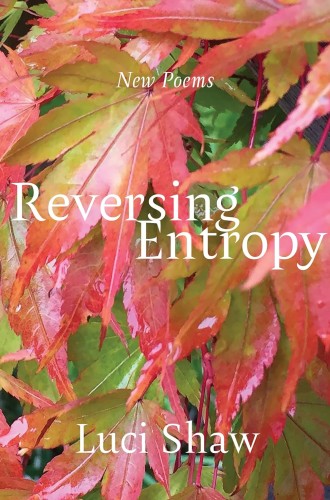

In Luci Shaw’s new collection of poems, ordinary objects trespass their boundaries.

Reversing Entropy does so by constant motion and by linkages within that motion. Even in the orderly heavens, the poet catches a wandering star through the skylight in her room. The birds fly. The clouds move. Rain falls. There is movement from one element into another—synesthesia, it is called in “Lilies of the Valley,” where the flowers’ fragrance becomes music.

Luci Shaw’s new collection is a magical world of daily bread where ordinary objects trespass their boundaries. Sheets on a backyard clothesline become wings, catching the development of metaphor or the afterimage of a further image, the clothesline as a branch with wide white leaves. There are the movements of the seasons: a blunt twig-end becomes bud, becomes blossom, becomes berries, becomes twig again. There is movement of moss across a rock. Lichens jump to images of bicycles moving. In “Driving Through the Season,” Shaw passes an ancient barn “leaking daylight.” Always the observer, and always the arranger of those observations.

Shaw is a seer of likeness between things not alike. The rock wall rises like a giant’s shoulder. Even in the stillness of a car, her pencil moves to take notes, to make similitudes—or the unexpected unlikenesses—as when “stabs / of sunlight” pierce us with an understanding of the gravitas of our world, or the too-bright sun through a windshield catches an open eye not prepared for its sudden intrusion.