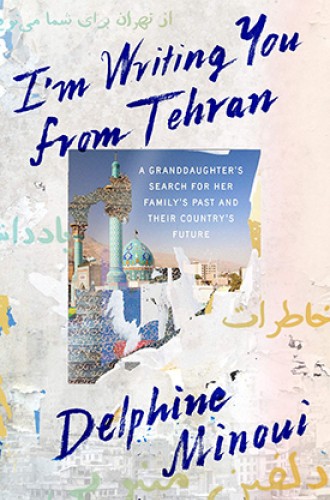

Learning to love Iran

Delphine Minoui planned a weeklong visit to explore her heritage. She stayed for 10 years.

Shortly before he died in 1997, Delphine Minoui’s paternal grandfather sent her some lines written by the 14th-century Persian poet Hafez:

He who binds himself to darkness fears the wave.

The whirlpool frightens him.

And if he wants to share our journey,

He has to venture well beyond the comforting sand of the shore . . .

The next year, Minoui, the daughter of a French mother and an Iranian father, decided to travel to Iran for a week to connect with her heritage and begin working as a journalist. Her weeklong trip turned into a ten-year stay and led to the writing of this compelling memoir, written as a letter to her grandfather.