James Martin offers a primer for prayer

His definition of prayer is simple: conscious conversation with God.

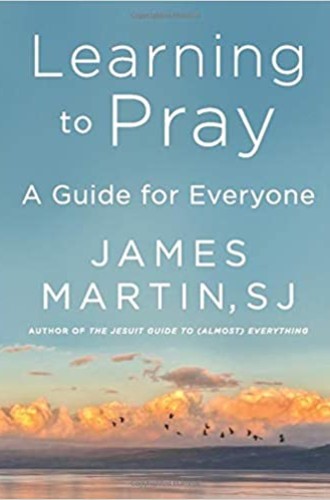

The tradition of writing prayer guides reaches back to the early centuries of the church, to Origen and Evagrius and to the many treatises on the Lord’s Prayer by church fathers. The tradition has continued into recent decades, with popular books like Richard J. Foster’s Celebration of Discipline and Marjorie J. Thompson’s Soul Feast. Because each generation needs instruction in prayer that is contemporary and accessible, we are fortunate that James Martin has written Learning to Pray: A Guide for Everyone.

Martin, a Jesuit priest, is the author of a number of books on the Christian life. In this one, he brings deep learning, his own experience of prayer, and wisdom gleaned from many years as a spiritual director to bear on fundamental questions of prayer: Why pray? What is prayer? The early chapters clear this conceptual ground, but Martin’s writing is never heady or esoteric. Throughout the book, he shifts effortlessly from theological explanation to practical advice.

Though the book is subtitled “A Guide for Everyone,” Martin writes with beginners in mind. A winsome and gentle guide, he lowers the bar for those who seek a life with God but struggle to begin or persevere. While he discusses the pros and cons of many traditional definitions of prayer, in the end he offers his own simple definition: “Prayer is a conscious conversation with God.” He appreciates more expansive accounts of prayer that affirm that all of life can become prayer, but he focuses his attention on those intentional times set aside for communicating with God.