The ghosts and the not-yet-dead

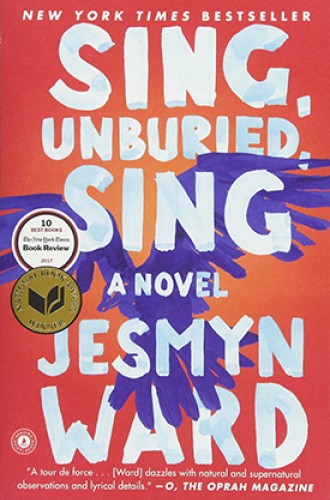

Jesmyn Ward’s novel is a descent into hell on earth. I couldn't put it down.

MacArthur “genius grant” winner Jesmyn Ward seems incapable of writing a boring scene—or if she ever wrote one, she had the good sense not to put it in front of her readers. I read Sing, Unburied, Sing with uninterrupted fascination and emotional investment, with that elevated heartbeat we feel when we know we’ve found an author really worth our time. This in spite of the fact that the novel is an unrelenting record of sufferings, one child abuse or lynching or torturing by butchery or prison rape or bad trip or cancer death after another. It’s a descent into a hell on earth, but one that deserves our attention because these sufferings are real in our America.

At the heart of the novel is one of the most beautiful relationships I can recall encountering in a recent literary work. Jojo, the 13-year-old son of a white imprisoned father and an African American drug-addicted mother, must take round-the-clock care of his three-year-old sister, Kayla, for the pathetically sad reason that their mother does not care much about them. Jojo is a naturally loving, patient parent figure. Again and again, he cleans up his sister’s vomit, comforts her in her febrile crying, rocks her to sleep, and connives to find food for her when she wakes. He carries her out of the reach of their abusing father. Loving his sister continually is Jojo’s calling and his gift. For Kayla’s part, she humanizes her big brother by giving him this work of love to perform and by loving him back.

Love is complicated and unsentimental in this novel. Jojo calls his mother by her given name “Leonie” because he will not admit that she has ever behaved toward him as a mother should. Leonie’s mother, Mam, admits on her deathbed that she realized Leonie “ain’t got the mothering instinct” when they were out shopping together and Leonie ate a snack in front of baby Jojo, who sat there unfed and “crying hungry.” “I knew then,” says Mam.