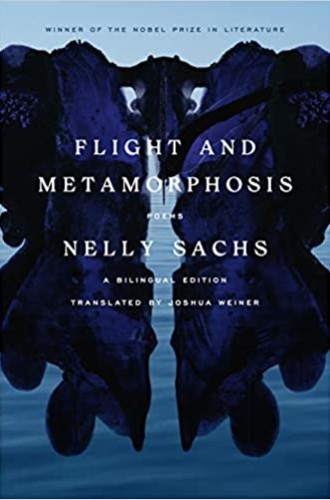

A fresh translation of Nelly Sachs’s later poems

For Sachs, flight is multivalent: her flight from the Nazis, any refugee’s flight from oppression, God’s flight from God.

Nelly Sachs, a Nobel Prize winner widely known for her poetry about the Holocaust, was a secular German Jew who escaped from Germany with her beloved mother in 1940 and spent the rest of her life in Stockholm, living modestly in a cramped apartment. She had endured a Nazi interrogation that left her unable to speak for several days afterward. Her lover, a member of the resistance, was thought to have been executed in front of her. Having lost her home, citizenship, and identity, she suffered from mental illness—especially after the death of her mother. But she continued to write.

Flight and Metamorphosis, a collection of the poems that followed Sachs’s famous poems on the Holocaust, was first published in 1959. Most English-speaking readers are unfamiliar with these poems, even though they have existed in translation for many decades. In this bilingual edition, Joshua Weiner not only provides fresh translations of the poems, he has also included notes on many of them and a helpful introduction. The notes are essential, especially for readers unfamiliar with the Zohar—the most important work of Jewish mysticism.

This is a collection that should resonate with contemporary readers because of Sachs’s emphasis on homelessness, dislocation, exile, longing, flight, and (yes) metamorphosis, which is hard-won through suffering and usually incomplete. The book is disorienting, containing the upheaval of thought and language experienced by the refugee. God in these poems—the Deus absconditus—seems to have withdrawn into God’s self. The flight is multivalent: it is Sachs’s flight from Germany; it is God’s flight from God; it is any refugee’s flight from oppression; it is the soul’s flight.

How many homelands

play cards in the air

as the refugee passes through the mystery

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Everything is endless

and hung on the rays

of a distance.

Geheimnis (mystery or secret) is re-peated over and over again in these poems. At the center of that German word, Weiner points out, is Heim (home). That is what the poet seeks and never quite finds. Homesickness and unrest are constant; longing is rampant; home and rest seem impossible. “Rest,” Sachs writes, is “only a dead oasis-word.”

Still, the poet waits. Addressing God, she says:

I wait for you

who linger, far from the living

or near.

Turned away

I wait for you

since those who’ve been freed

cannot be captured

by coils of longing

or crowned

with the crown of planetary dust—

love is a plant in desert sands

it serves in fire

and is not consumed—

Turned away

it waits for you–

The desert sands refer to Israel’s time of exile, wandering, homelessness. God’s light is present in the burning bush. Still the poet waits. Even the burning bush waits.

Of all of these poems, “Child” will have the most terrifying resonance for contemporary readers familiar with the heart-wrenching photo of the drowned Syrian child on the shore of the place of refuge:

Child

child

your head buried now

the seedpod of your dreams

grown heavy

in final surrender

ready to sow other land.

With eyes

turned back toward the motherground—

You, cradled in the century’s rut

where time with ruffled wings

drowns, stunned

in the great flood

of your endß

without end.

These poems contain questions, contradictions, paradoxes. They define fear as a tactile quality: “in fear, a seed sprouts / quick on a human finger.” They describe sleep as the only true refuge for the refugee, “the hiding place with no tears.” “A stranger,” Sachs writes, “always has / his homeland in his arms.” But the stranger is “like an orphan / for whom he may be seeking nothing / but a grave.” The images amass, a midden of discomfort, unsettledness, and dread.

These poems are not easy, but they reveal their layered meanings to the persistent reader. Because of my unfamiliarity with the Zohar, I sometimes felt I was reading through a veil. But then the veil would lift and the brilliance of image, language, and thought would blaze forth. With this volume added to her Holocaust poems, Sachs takes her place among the 20th century’s most important poets, as the Nobel committee recognized several years after its first publication.

The final poem in the collection finds the poet with “arms outstretched,” trying to “weigh the fleeing.” Here once again is the flight of the title. But then the metamorphosis. She writes, “Deep dark is always the color of longing for home / so night takes me again / into its domain.” The longing itself has become home. And night is the ruler of that land.