FDR’s faith

John Woolverton addresses a gap in Roosevelt scholarship with elegance and insight.

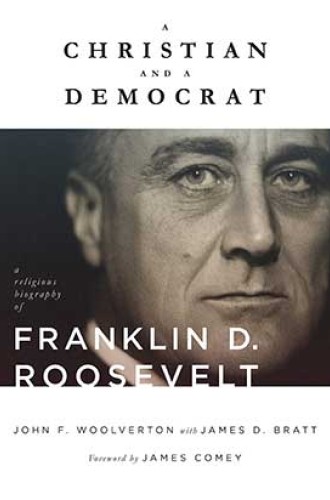

Once when a reporter asked President Franklin Delano Roosevelt the source of his political views, he hesitated and then replied, “I’m a Christian and a Democrat.” Years later, a family friend described him to his wife, Eleanor, as “a very simple Christian.” Eleanor raised her eyebrows and responded, “Yes a very simple Christian.”

Though American historians often see Roosevelt as one of the nation’s finest presidents, they have paid surprisingly little attention to his religious ideas and practices. John Woolverton addresses that need with impressive erudition, elegant prose, and clear insight into the larger implications of the story. When Woolverton, an Episcopal priest and scholar who taught at Virginia Theological Seminary, died in 2014, he’d nearly finished writing this book. James Bratt, who teaches at Calvin College, completed the volume by cutting some details and adding a moving chapter on FDR’s death and funeral.

Roosevelt’s career offered a capacious stage for the exhibition of his religious instincts. Born in 1882 of patrician parents in Hyde Park, New York, he matriculated at Groton Preparatory School, Harvard College, and Columbia Law School. Though he was an indifferent student academically, his wealth, athleticism, family connections, voracious reading, and charismatic personality opened doors. In due course he became a New York state senator, governor of New York, assistant secretary of the Navy, and four-term president of the United States (the latter two terms unprecedented). He died in April 1945, just months before the end of World War II, at age 63.