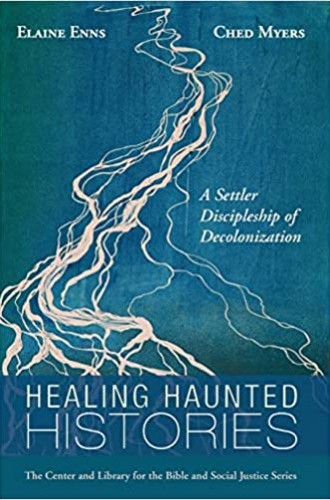

Elaine Enns and Ched Myers explore a theology of restorative solidarity

How can a people paralyzed by facing its history move forward?

This profound, timely, humbling, but ultimately empowering study is exemplary in every way, offering a path through thickets of intense debate and hope amid cacophonies of denial and anger. The fruit of Elaine Enns’s ten-year quest for an Anabaptist discipleship of decolonization and Ched Myers’s lifetime of soaking scriptural exegesis in practices of restorative solidarity, this sequel to the pair’s impressive two-volume Ambassadors of Reconciliation is a landmark statement on how a people paralyzed by facing the horrors of its own history can go on. For every contemporary quandary of the penitent church, Enns and Myers offer true solidarity (in place of sentimental compassion), riveting analysis (in place of lazy generalization), and practical steps (in place of depressed inertia). It’s an emotionally intelligent, culturally aware, refreshingly prescient gift to a confused, dispirited church.

Enns’s 18th-century forebears left Prussia for the Russian steppe, responding to Catherine the Great’s invitation to cultivate the soil but paying less attention to the people who were driven out to make that steppe available. These German-speaking Mennonites, preserving their subculture, then scattered in the face of the Russian Revolution, fleeing across Russia, dying by slaughter, or making their way to the Canadian plains. They were a people without a land, but the land they came to possess was not without a people.

With a deft hand, Enns traces, in gripping detail, the history of trauma her people endured—but never excuses the trauma those same people, and Canada as a whole, inflicted on the Indigenous residents of Saskatchewan and neighboring provinces. This is the tragic irony at the heart of the book, and perhaps at the heart of North America: the settlers’ acute awareness of their own trauma and of the fertility of opportunity around them—alongside their inability to perceive the corresponding experience of the native peoples among them or to honor the treaties they signed when they did.