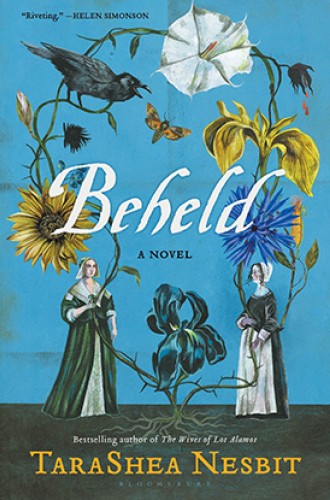

Discord on Plymouth Rock

TaraShea Nesbit’s novel about the Mayflower pilgrims and their conflicts

My office is situated about 100 feet away from a sliver of Plymouth Rock, which the congregation inherited from Chicago Theological Seminary several years ago when the school relocated. We received the rock with considerable fanfare: church members dressed up in full Pilgrim regalia for the presentation, and we immediately hired a stone mason to embed it into one of the church walls. We’re not the first Congregationalists to take Puritan history so seriously. CTS is said to have received the rock after the Columbian Exposition in 1893, where it had been displayed to honor the role of Congregationalism in the formation of democracy.

Beheld is a story of Puritans, but not Puritans alone. Indeed, the spare book—like the historical Plymouth—is diversely populated. TaraShea Nesbit explains in the author’s note:

In telling this story, I wanted to add more possibilities to our collective imagination about "the pilgrims." I also wanted to challenge certain myths, such as the belief that all the Mayflower passengers were seeking freedom to practice their religion. . . . The people on the Mayflower arrived to Patuxet from a variety of backgrounds and for different reasons—indentured servants who signed up out of various necessities, craftsmen hired to assist in the physical creation of the colony, people looking for economic gain, . . .