Did Christianity destroy classical pagan culture?

Catherine Nixey is right: the early Christians were violently destructive. So were the Romans, the Persians, and the plagues that swept across the ancient world.

Gore Vidal’s 1954 novel Messiah presented a grimly satirical perspective on Christian history. It imagined a near-future world in which Christianity is challenged and overthrown by a doomsday cult founded by John Cave (“JC”), whose fanatical followers establish their faith by ruthless acts of brutality against Christian people and their places of worship. Drawing on his extensive knowledge of Christian violence against pagans in the Late Roman Empire, Vidal was asking, in effect, how would contemporary Christians like it if the same things happened to them?

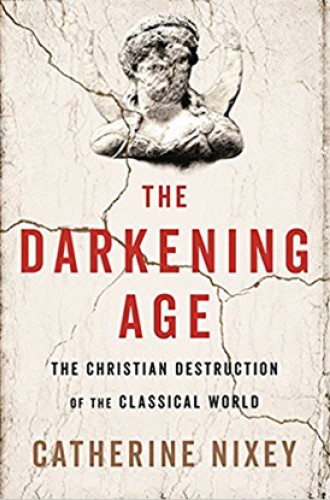

A similar anger about historical Christian atrocities drives Catherine Nixey. Although The Darkening Age is harshly polemical and poorly connected to mainstream scholarship, it makes some valid points about violence, intolerance, and iconoclasm in Christian history. Assuredly, it will serve as a major weapon in the arsenal of antireligious polemic for years to come.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Nixey powerfully describes the ruthless destruction of pagan temples, shrines, and institutions in the century after Constantine’s decision to tolerate the new faith. The perpetrators were often monks, a “marauding band of bearded black-robed zealots” who in Egypt and parts of the Levant acted as private militias, beyond the control of civil institutions. Many of their actions, such as their attack on the pagan remains of Palmyra, seem alarmingly familiar in light of the recent horrors perpetrated by the Islamic State. Monks then, like extreme Islamists today, saw temples and statues not as cultural heritage but as flagrant manifestations of polytheism and diabolism.

While their actions were not defensible, the monks were correct to see the pagan shrines as a major obstacle to Christianization. People would continue to believe in the power of the old gods and spirits until their sacred places were removed. The power of the old gods ended at the moment Christians wrecked their idols and survived unscathed. This same dynamic motivates contemporary Christian congregations in Africa, where paganism and animism are still vibrant forces, and where recently converted Christians ceremonially burn fetishes and pagan artifacts.

In focusing on historic acts, Nixey helps us recall the central role of iconoclasm in the Christian past. However often we tell the Reformation story in terms of books and learned controversies, the movement had its main popular impact only when mobs stormed the churches and cathedrals and purged the holy pictures and statues. Across faith traditions, tectonic religious shifts are repeatedly marked by a rejection of the material and a turn to more inward-directed perceptions of spiritual power. From the time of the biblical King Josiah onward, iconoclasm has been the foundation of reformations.

Nixey recounts horrible stories of mob violence not only against beautiful old buildings and precious manuscripts but, far more seriously, against pagan individuals. She discusses the ghastly mob murder of the philosopher Hypatia in Alexandria in 415, an atrocity that has become central to a modern-day secularist hagiography.

Having said that, the book accomplishes far less than its author and publisher claim. Anyone with any knowledge of early Christian history already knows this story in broad outline. When Nixey says it’s a story nobody has ever told, she’s forgetting about Edward Gibbon—and a couple hundred more recent successors.

More troubling is the rosy account she offers of the pagan world that Christians struggled against. She depicts classical paganism as a gloriously rich culture marked by almost limitless tolerance of other faiths, except where those were evidently criminal or seditious. She minimizes the experience of Christian martyrdom to trivial proportions. She stresses the astonishing scientific achievements of that ancient pagan world, drawing a stark contrast with Christian obscurantism. Paganism, Nixey implies, is simply a better way of living than monotheism.

But she is not comparing like with like. Her portrait of classical pagan culture draws heavily on the Golden and Silver Ages, from roughly the second century BC to the second century AD. But that older world of Ovid and Horace was in ruins by the time of Constantine—and Christianity had nothing to do with the collapse. For reasons that were variously social, political, and economic, classical culture and literature were already in terminal decline, and scientific innovation had slowed dramatically. The pagan religious thought of Late Antiquity was widely marked by pessimistic and world-denying attitudes that condemned the material creation. This was the intellectual paganism that Christians confronted.

When historians today use the term Dark Ages, we generally restrict it to specific and narrow eras that affected some limited regions, where civil society collapsed for decades or even centuries. Nixey, though, regards the Christian curse as poisoning Western history far beyond the immediate post-Roman centuries. She characterizes the Dark Ages of scientific repression as extending through “a thousand years of theocratic oppression,” up to the Renaissance or even the Enlightenment. No serious academic historian is likely to support this view.

Further, any reasonable account of the decline of classical civilization would focus not on the time of Constantine and his successors but rather on the lengthy period between about 230 and 560 AD. It would address a variety of factors: climate change, due in part to some titanic volcanic eruptions; repeated plagues on a scale comparable to Europe’s Black Death; and the collapse of Roman frontiers which permitted the mass incursion of pagan barbarians, whose depredations destroyed countless ancient cities and texts. Nixey mentions those factors briefly but only to dismiss them as minor in comparison to the malignant growth of the tumor that was Christianity (much as had Gibbon before her).

When contemplating Nixey’s view of this era, we might remember the Christian monk Gildas, who around 540 attempted to reconstruct the history of his British homeland. He could find no written works, as all had perished under the pagan assaults on the old (Christian) Roman cities. Insofar as Dark Ages can be traced to particular times and places, they occurred for reasons quite unconnected with the spread of Christianity. In fact, the Christian role in such crises was to pick up the pieces of civilization.

In the eastern Mediterranean, the mighty Hellenistic city of Antioch dominated prosperous Syria and served as a transcontinental center of learning and scholarship. Antioch’s cultural role was quite unaffected for two centuries after the coming of Christianity, until the city was successively devastated by the appalling earthquake of 526 and the invading Persians in 540. If by happenstance Antioch had retained its original glory for a few more years, many thousands of its citizens would have perished in the subsequent pandemic known as the Plague of Justinian.

The ruin of Antioch cast a long shadow across a once-flourishing region. Most of the other great cultural centers of the Middle East were crippled by the long Roman-Persian wars of the early seventh century, followed immediately by Islamic conquests. During this crisis era, the Syriac Church of the East and other churches preserved and transmitted the intellectual treasures of pagan antiquity, including philosophy, science, and medicine. Eastern Christian centers like Nisibis and Gundeshapur became the cultural treasure houses of the age. Christian monks and clergy then translated those works for their Islamic conquerors, who subsequently bequeathed them to Christian Europe, thereby making possible the intellectual triumphs of the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance.

This story may sound a lot like the familiar stereotype of Christian monks keeping alive the guttering flames of ancient civilization, a narrative that Nixey repeatedly mocks as a self-serving Christian fable. She would not do so if she had any grasp of the millennium following the fifth century. Some stereotypes are grounded in history. Others, like those that Nixey relies upon, are not.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Christian v. pagan.”