Diane Glancy’s search for home

Glancy’s spirit is shaped as much by her exile from her tribe as by her ties to it.

In a 2019 interview in Image, Diane Glancy revealed that “Acts of Disobedience” was the working title for this collection of essays. She defined her three acts of disobedience as her “unorthodox way of writing,” her self-avowed fundamentalist Christian faith, and the miles of driving she logs each year. Glancy is an essayist, storyteller, poet, and playwright who articulates the pain of her Cherokee heritage and the solace of her faith in ways that press the edges of literary experimentation—and thwart the expectations of some readers. A Publisher’s Weekly reviewer once panned both her writing style (a “mishmash of words; unnecessarily obtuse”) and her “endless pontifications upon Jesus and the role of Christianity in her life.”

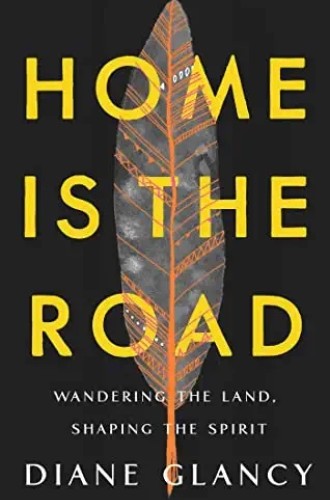

Home Is the Road is a better title for this book, which is structured by the ground Glancy covers while pondering the shape of her family legacy and her spirituality. Throughout the book, she weaves biblical references and imagery into Native creation and origin stories, spinning a nonlinear memoir that is part poetry and part prose.

Glancy speaks to us from the highways between her home state of Kansas and her destinations at writing conferences, residencies, film festivals, and a few family visits. She logs long hours in the car, stopping only briefly for food or fuel, grabbing a few hours’ sleep at rest stops in the night as she traverses the land and tells us stories that shape her spirit.