A deep history of women’s cultural criticism

Michelle Dean's book isn't exactly a group biography. But it is a highly entertaining feast of quotes, anecdotes, and analysis.

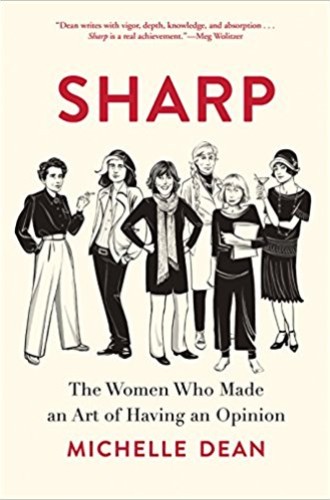

The person who picks up Sharp in the bookstore and gazes at its cover illustrations—line drawings of Hannah Arendt, Susan Sontag, Nora Ephron, Renata Adler, Joan Didion, Dorothy Parker, Janet Malcolm, Mary McCarthy, Rebecca West, and Pauline Kael—may wonder what sort of book it is.

It’s not exactly a group biography. It’s not a study of a single period or milieu, although certain editors and institutions show up more than once. It doesn’t trace out a single line of influence or sensibility: not all of the writers it discusses were even particularly interested in each other. (Adler famously flamed Kael. Kael mocked Didion’s hypersensitivity. McCarthy supposedly greeted Sontag at a party with “I hear you’re the new me.” I can’t begin to imagine what, if anything, Arendt thought of Ephron.)

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

It’s easy enough to draw connections between any two or three of them—Arendt and Mary McCarthy, in particular, shared an unusually noncompetitive and supportive friendship, with McCarthy giving up several years of her own working time to finish Arendt’s posthumous The Life of the Mind. But it’s hard to connect all of them via any idea less general than “They were all women who wrote brilliant, penetrating nonfiction.”

As this book goes on—and it is a highly entertaining one, a feast of great quotes, revealing anecdotes, and at least occasionally surprising analyses—Dean’s mission becomes clearer. She aims to show that intellectual journalism by women has a tradition. In group literary histories of this kind, women writers are often treated in isolation from one another or ignored entirely. Sharp shows women cultural critics that they have a larger history, and precisely at a moment that feels like a golden age for such writers. (Just among younger women, we now have Maria Bustillos, Kristin Dombek, Dayna Tortorici, Jia Tolentino, B. D. McClay, Tressie McMillan Cottom, Meghan O’Gieblyn, Amber A’Lee Frost, Elizabeth Bruenig, Hannah Black, Maureen Tkacik, Andrea Long Chu, Niela Orr, Clare Coffey, and Claire Jarvis all simultaneously walking the earth.)

Sadly, the tradition Dean gives to this new generation of writers is a largely middle-class and white one. Dean laments at one point that Zora Neale Hurston didn’t get the chance to write more nonfiction, but a longer consideration of the journalism and other nonfiction Hurston did write would have enriched this book’s story.

All the writers Dean considers had an ambiguous relationship with the women’s movement and other movements for social justice. Tracing this tension, it soon emerges, is Dean’s other major project here.

This part of the story, too, has its fascinations. It’s oddly moving to know that Dorothy Parker—whom pop culture often represents as a frivolous, brittle aphorist—lived a surprisingly committed life (she left her estate to the NAACP!). West was a suffragette. Ephron, perhaps the most actively political of them all, spent several years trying to maintain the private time and independence of judgment that a writer needs while also taking part in the constant swim of activity and communication that the second-wave feminist movement required. But for the most part, the women in Dean’s book aren’t joiners.

In the afterword, Dean argues that “there is room, in this deep ambivalence . . . to take away a feminist message.” Though feminism requires sisterhood, she writes, “sisters argue,” as these writers did—with themselves, with men, with other women.

I’d go further. In her capacity as a writer, no woman is a sister as second-wave feminism defined it, any more than a male (or other) writer, qua writer, can truly be a “comrade” in the socialist sense of the word. You can, of course, be these things in your capacity as an everyday person. But writing about them will require constant navigations back and forth across various tiny and hard-to-trace lines. And writing at all demands a level of control over one’s time—which is the first kind of control that one gives up when one fully commits to an activist campaign. The writer we like is a kind of distant friend—Muriel Spark said that she began her novels by pretending to write to the one friend who really got her—and friendship has a kind of built-in exclusivity. It is the hardest kind of relationship to subsume in a collective.

For the focus it takes, Dean’s book is a valuable and interesting one. But it’s marred by some slack phrases and the occasional fact-checking error. Most of these errors are trivial—for example, Dean writes that Adler quit publishing nonfiction in 1999, although she’s published at least three essays since then. But one of them is downright sinister. Here is how Dean describes the murder of Archbishop Óscar Romero, who was killed by a right-wing death squad under a military dictatorship: “By 1982, when Didion arrived in El Salvador, there was little question the Communist government of the country was a regime of terrifying violence. An archbishop was shot in the pulpit; massacres were being documented by photojournalists.” None of Dean’s writers were good at party discipline, but they at least tended to blame atrocities on the right people.