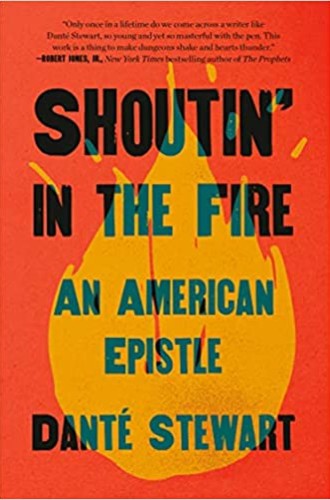

Danté Stewart’s letter to America

Shoutin’ in the Fire is a testimony to Black liberation and love.

Danté Stewart’s debut is a letter to America, a letter not of hatred but of hope. Like the Bible’s epistles, it is simultaneously an admonishment toward love and justice and a refusal to appease the power wielders and empires of the world. Stewart stands in the fire and calls his readers out of comfort, out of complacency, and into a new way of imagining our life together.

This book is guided by key moments of Stewart’s life across different spiritual, communal, and physical locations. From the smell of fried chicken floating up from the basement of his childhood Pentecostal church to the “nice white Christians” of evangelical megachurches in Georgia, Stewart invites readers to examine with him what it means to be Black and Christian in America, “caught between a terrifying and inescapable reality: the Bible, the country, and the body.” The primary theme that runs through the book—that “Black people are worthy of the deepest love”—unfolds in two movements.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The first movement highlights the lessons Stewart learned through his childhood in the American South and his migration into White evangelical spaces. He explains his early efforts to make sense of his story as a young Black man in America and the “cost of ‘making’ it in a white world” that cares only about Black bodies in performance or in pain. He describes pieces of his childhood in South Carolina, his experience as a college athlete at Clemson University, and the energetic evangelicals there who eventually led him into the doors of their White church. In this context, Stewart was deeply formed personally and theologically, rejecting the Black spiritual roots of his childhood for a John MacArthur brand of Reformed theology and the pulpits it offered. “I lost the Black world I came from,” Stewart writes, and “the cost didn’t matter. The rewards of whiteness were too great.”

The second movement recounts Stewart’s journey out of White evangelical spaces and back to his childhood home of Black Pentecostalism and prophetic activism. This movement is marked by a radicalization, a turn from complacency and appeasement to rage in the face of systemic injustice, lifeless Black bodies, and the apathetic reactions of White people. Immersed in the words and thoughts of Black writers like James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Martin Luther King Jr., James Cone, and many more, Stewart experienced an Ezekiel-like resurrection into radical Black love: “It was fire, burning, blazing, fire shut up in those bones. They came back to life; they rose again. I came back to life.” Inherent in this resurrection is an embrace of a Jesus who becomes good news to Black bodies “by remembering them, touching them and being touched, and creating a world where their bodies are liberated, redeemed, and resurrected.”

Stewart’s text stands in a long lineage of Black spiritual autobiographies. From Frederick Douglass to W. E. B. Du Bois to Harriet Jacobs to James Pennington, Black folk have for centuries reflected their lives and the stories of oppression and liberation that their bodies carry. These authors assert the humanity and dignity of their Black bodies without merely reducing their lives to resistance or lessons to be learned. Shoutin’ in the Fire, like many of its predecessors in this genre, boldly claims in an anti-Black world that “Black people deserve love. Black people don’t deserve bullets. Black people deserve tenderness. Black people don’t deserve terror.”

Stewart’s words cultivate beauty in its truest sense: the stories and pictures woven together in this book make us feel something. The book is also incredibly readable. It is one of those books that you begin to read and, after what feels like minutes, look up to find hours have passed by.

Yet it is also incredibly difficult. Stewart’s lyrical storytelling can be disarming when describing the old back roads of South Carolina or the sweet joy of his son, but the same skill leads to gut-wrenching horror, sadness, and grief as he describes his experience as a young Black man in America and the death and destruction he bears witness to. Stewart doesn’t shy away from immersing us in these experiences too.

Shoutin’ in the Fire is not a set of answers to how White evangelicals might act better or how White folks can be antiracist. Problem-solving is not at the heart of this book. Instead, it is written for those who are held captive by a world that does not love them. From the fire Stewart shouts with passion and conviction, fervently declaring that God cares for and loves Black bodies, even when our world does not. Like those Black autobiographers before him, he offers a prophetic condemnation of the systems, structures, and institutions in our world that perpetuate the abuse, marginalization, and oppression of Black bodies. In return, he turns sorrow into meaning through “the audacious belief that one’s body, one’s story, one’s future does not end in this moment.”

Some critics might argue that Stewart’s depiction of White-governed spaces, and particularly evangelical ones, is uncharitable or unproductive. But neither charity nor productivity is the purpose of Stewart’s epistle. Prophecy is. Stewart states that he is done arguing with White folks, “people who said they loved Jesus . . . who said that they wanted reconciliation . . . who said they cared about our suffering.” His project is not an attempt to prove his humanity or the validity of his experiences.

Shoutin’ in the Fire is an ongoing story of liberation and Black love in which we may find both pieces of our own story and hope for a better future. It is prophetic, masterful, and Spirit-filled. It is a true gift to the church.