Da Vinci was many things, but not a productivity guru

Walter Isaacson offers a clear and enjoyable biography. He also offers life hacks from Leonardo.

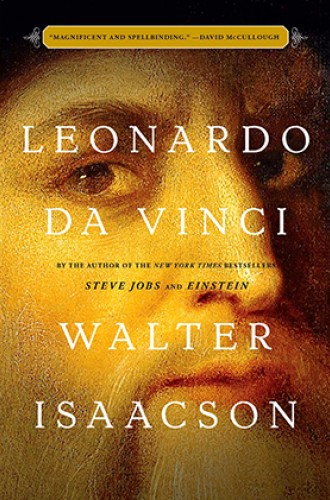

As a literary genre, biography seems straightforward: it offers the available facts about an individual’s work, victories, defeats, relationships, and more. At its best biography allows readers to get as close as possible to knowing a person without ever coming into actual contact with him or her. Walter Isaacson’s hefty new biography of Leonardo da Vinci gives us a good idea of how the artist and thinker presented himself in his notebooks, how he navigated the knotty world of patronage and politics, how he transformed artistic practice and unraveled scientific problems, and what he may have been like as a person. But Isaacson’s method of doing so raises questions about what motivates the writing and reading of a biography.

It’s not that Leonardo da Vinci is incomplete in any way. I can’t imagine a reader coming away from this beautifully illustrated, 600-page volume feeling cheated out of essential information, either about Leonardo himself or about his time, the places he lived, his circle of friends, colleagues, and patrons, or his newly rediscovered works, such as Salvator Mundi or La Bella Principessa. Nor does Isaacson rebel against standard form or style; the book is a plainspoken presentation, mostly in chronological order, of the life and work of the 15th- and 16th-century artist and thinker. Leonardo is a clear, generally enjoyable read that, in addition to painting a picture of the master’s interdisciplinary work and thought, emphasizes the importance of not pitting the arts and sciences against each other.

I eventually grew uncomfortable, however, with Isaacson’s periodic admonitions “to be more like Leonardo”—to stop and smell the proverbial roses just because they’re there, or to marvel at dust motes in sunbeams and the workings of a lowly cogwheel. And most readers probably do need a reminder to slow down and notice the world.