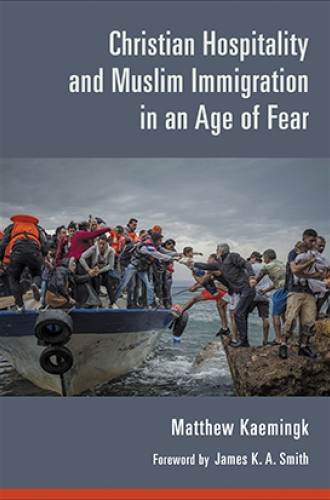

If you were looking for an argument for welcoming strangers of another language, religion, and race, you probably wouldn’t seek it from an American evangelical Christian. But that is precisely what Matthew Kaemingk gives us in his startling new book. Given the political harm American evangelicals have recently wrought in the world, it is thrilling to find this counternarrative.

The background of the book is familiar: while political correctness demands that people speak no ill of cultural newcomers, frustration and resistance to this stance erupts in xenophobic vitriol. But Kaemingk isn’t writing about Latino immigration to the United States. His topic is Muslim immigration to the Netherlands, rooted in his doctoral research in Amsterdam. The Dutch, proud of their reputation for being liberal and inclusive, run face-first into the conservative Islam adhered to by immigrants in ways that are both nationally traumatic (as in the 2004 assassination of filmmaker and critic of Islam Theo van Gogh) and quotidian (hijabs on the streets of Amsterdam).

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

For Kaemingk, both the left and the right in Holland have failed in their approach to immigration. Muslim workers were first brought to Holland after World War II to do menial jobs, and they were kept in secluded work camps. When it became evident that they wouldn’t return home, these immigrants were encouraged to assimilate to Western and liberal values. When they would not, the Dutch proved to be as intolerant of difference as many other groups—and nationalist politicians took advantage.

American right-wingers have avidly brought Dutch filmmaker Ayaan Hirsi Ali and political fulminator Geert Wilders into their media to proclaim Dutch multinationalism a failure in the face of “radical Islam.” Heads of state in Britain, France, and Germany agree on the need for a more “muscular” liberalism against a group that has infiltrated the West by the millions.

Kaemingk notices a pattern. The question asked by both liberals and conservatives is what Muslims must do to integrate into Europe. No one asks what Europe must do to welcome Muslims. The presumption is that secular liberalism is the unquestioned hegemonic power: take off those hijabs.

Kaemingk isn’t surprised at liberalism’s failure. Every ideology can become hardened and brittle once in power; that’s precisely why we need multiple competing interests. Western Europe once figured it was the eschatological culmination of all history: with brutal religion left behind, tolerance and multiculturalism were unquestioned and unquestionable. No longer. Kaemingk observes: “a small group of veiled Muslim women walking down the Champs-Élysées confront the young, secular Parisians they pass with a series of questions many of them have never asked during their young lives.” The hijabs challenge secular presumptions.

So what’s the answer? There is none writ large. Kaemingk professes to write for Christians, not to offer universal truths. Yet he finds a resource in a surprising place—the 19th-century Dutch Reformed theologian and politician Abraham Kuyper.

Christians in Holland and America have often dropped their distinctiveness in attempting to show the world they can be tolerant. Kaemingk’s response is not hostile, but it is accurate: these churches win some outside respect but few converts. At the other end of the spectrum, right-wing Christians just parrot their secular counterparts in the culture wars. Kaemingk presents Kuyper as someone as christologically anchored as the conservatives, which enables him to be more pluralist than the liberals. He allows for an “uncompromising commitment to the exclusive lordship of Jesus Christ” and also “an uncompromising commitment to love those who reject that lordship.”

Kuyper is not always presented this way by his fans or foes. His notion of “sphere sovereignty,” in which the church and the world are ruled by Christ in quite different ways, often ends up reinforcing the same separation of church and state that marks Western liberalism generally. Nicholas Wolterstorff, often lauded in Kaemingk’s work, can opine for hundreds of pages at a time with nary a mention of Jesus. On this issue, there is an intramural fight within Kuyperian circles.

What’s appealing about Kaemingk is he doesn’t get bogged down in these arguments. He just speaks to the church and the world with a word both need to hear: Jesus is Lord. Christians must offer the hospitality to the other that Jesus offers to us. Kaemingk borrows from Stanley Hauerwas (not a frequent resource in Wolterstorff) to suggest that the liturgy for holy week offers a pattern for Christian love, multiculturalism, and welcome to the other without expectation of conversion or even a peaceable response.

The best part of the book is its accounts of ordinary Dutch Christians offering kindness to Muslim neighbors simply out of love for Jesus. One pastor stood guard outside his neighborhood mosque after the riots that followed the Van Gogh murder. Was he sympathetic with Muslims? A liberal? None of the above. He was a Christian commanded to love even his enemies. A group of Christian and Muslim women started an interreligious dialogue and wound up sewing together. The more modest goal took the pressure off and led to friendships.

The Free University, founded by Kuyper but now as secular as any other, hires for its religion department committed believers from multiple faiths instead of believers in nothing. Calvinism (of all things!) allows Dutch Christians to befriend the stranger without pushing Jesus. If God elects people to salvation despite our efforts or lack thereof, why feel any pressure to convert someone? Kaemingk proposes a “Trinitarian pluralism” wherein Christ alone is judge, the Spirit is at work in all cultures, and the Father is creator of all. Here Christian commitment need not be set aside to love the other. It is its very prerequisite.

No single book can answer everything. We learn little here about Muslims’ own beliefs, aside from a fascinating vignette in which a church plant invited immigrants to dinner and were refused. When they instead asked immigrants to host them, they were warmly welcomed, invited in, and cooked for. I’d love to hear more from those immigrants who have been embraced by Dutch Christians and the friendships that have resulted.

Some will argue that evangelical beliefs have yielded the xenophobic madness that marks politics on both sides of the Atlantic. But Kaemingk has marshaled enough evidence to say that it need not be so. Christians have someone to obey other than the stock talking points of the left or the right. The fruits are stories as surprising and delightful as Kaemingk’s.