Catholic sisters and their difficult vocation

Alice McDermott ponders a mystery: How is it that women hear the calling and find the strength to love and support their neighbors?

Alice McDermott offers an elegant and moving book about the mystery of women’s callings. Telling the story of a houseful of nuns (but they’re fun nuns!) in early 1900s Brooklyn, McDermott focuses on the indigent poor and working poor in a time marked by stunning wealth and wage inequality. As she shows the strength and inventiveness of women battling poverty and then plunges a few of these women into a moral and ethical dilemma, she seems to be pondering this mystery: How is it that women—especially Christian women in urban America—hear the calling and find the strength to love and support their neighbors faithfully in a harshly competitive country?

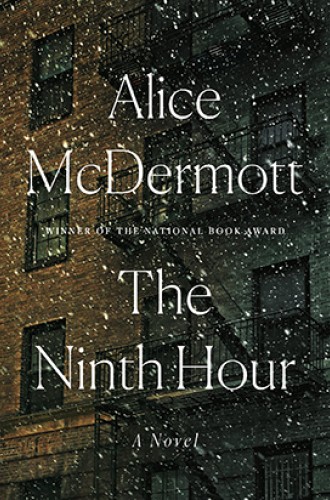

McDermott won both a National Book Award and an American Book Award for Charming Billy (1998), which, like The Ninth Hour, begins with the problems of a wayward alcoholic Irish husband in Brooklyn who’s in love with a beautiful immigrant girl—and a little in love with death. McDermott knows how to tell a compelling story, think freely about the Christian life, and write in a beautiful yet casual prose. (Think of Louise Erdrich, or Jhumpa Lahiri, or a Willa Cather who loves stylish sentence fragments.)

In this novel, McDermott seems at first a kind of historian of social welfare. Her nuns not only work tirelessly for those in need, but they model a compassionate and professional form of social welfare. The state did not provide it, so Catholic sisters did. These sisters are effective nurses, laundresses, teachers, daycare providers, money raisers, cooks, administrators, and theologians. They are remarkably selfless—one nun not even allowing herself a bathroom break during her hardworking day, others cleansing vomit and blood stains from bandages and clothing day after day. McDermott reminds us that there never was a moment when America didn’t need a social welfare system staffed by dedicated professionals.