The black social gospel and the civil rights movement

Gary Dorrien chronicles the influential—but often forgotten—work of Mordecai Johnson, Benjamin Mays, and Howard Thurman.

Pick up any general survey of Christianity in America and turn to the section on the social gospel. It is likely that the narrative will be dominated by the names of two white pastors: Washington Gladden and Walter Rauschenbusch. Along with some other lesser-known white social gospel Protestants, they sought to Christianize America through reforms, government programs, and voluntary societies designed to address poverty, disease, immorality, and all forms of injustice resulting from industrialization, urbanization, and immigration.

It is highly unlikely that the names Mordecai Johnson, Benjamin Mays, or Howard Thurman appear alongside Gladden and Rauschenbusch in the typical textbook narrative. But according to Gary Dorrien, these leaders of the black social gospel movement represented an intellectual tradition in American Christianity that was “more accomplished and influential” than the white movement led by Gladden and Rauschenbusch.

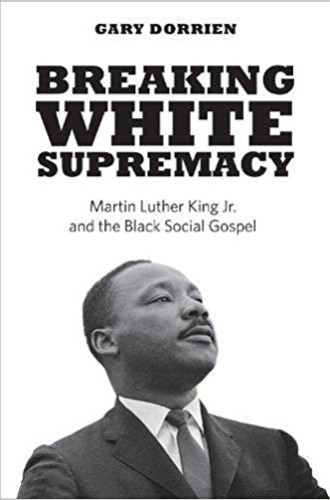

Breaking White Supremacy is a deeply researched and beautifully written extension of Dorrien’s award-winning The New Abolition: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Black Social Gospel, a study of the roots of the black social gospel movement. In fact, it is really two books in one: a history of the black social gospel as it unfolded in the years between Du Bois and the civil rights movement, and a history of how this movement influenced Martin Luther King Jr. in the years between Montgomery (1955) and Memphis (1968). The final two chapters focus on the legacy of the black social gospel in the work of theologians J. Deotis Roberts and James H. Cone and the women’s rights lawyer Pauli Murray.