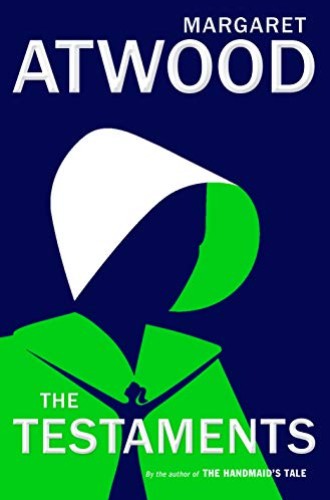

Back to Margaret Atwood’s Gilead

The Testaments returns to the world of The Handmaid’s Tale. Is this a good idea?

“Who would have thought that Gilead Studies—neglected for so many decades—would suddenly have gained so greatly in popularity?” So marvels a fictional historian in the postscript to The Testaments, the sequel to Margaret Atwood’s 1985 classic The Handmaid’s Tale, about a totalitarian theocracy named Gilead in which fertile women are forced into childbearing.

The historian is speaking to a gathering of academics in the distant year of 2197, but one imagines Atwood might have muttered similar words to herself in 2017. The Trump administration was busy making social progressives extremely nervous as it set out to dismantle Obama-era policies. Meanwhile, Hulu was resurrecting Atwood’s misogynistic theocracy on the small screen, taking viewers on a harrowing pilgrimage through their political nightmares.

In a review of the television series for the Christian Century, Kathryn Reklis warned that “finding too close a comparison between our current political situation and the dystopian fantasy is a genre mistake.” Still, it is unsurprising that Gilead re-entered the zeitgeist with an especially anxious vengeance. Protesters at the first Women’s March chanted “Make Margaret Atwood fiction again,” the Handmaids’ iconic red cape and white cap became a common sight at political rallies, and any number of Internet startups began selling t-shirts emblazoned with “Nolite te bastardes carborundorum,” the mock Latin phrase (“Don’t let the bastards get you down”) that gives the heroine hope on her hardest days of state-mandated rape.

The Testaments unfolds 15 years after Offred signs off as the titular narrator of The Handmaid’s Tale. Engrossing if uneven, the sequel is narrated by three women of shifting identities and loyalties: Aunt Lydia, Agnes Jemima, and Jade (aka Daisy). The tripartite narration works well as a plot device, tidily braiding a story that otherwise might have been a tangle. The thing about a braid, though, is that you generally know what to expect. I’m someone who can be shocked when love interests reconcile at the end of a romantic comedy, yet I saw certain revelations in The Testaments coming from a mile away. Some of the book’s many plot twists are deliciously inevitable, while others veer into mere predictability.

In Gilead, the Aunts are the authoritarian figures who discipline and train the Handmaids. The motivations of a character as villainous as Aunt Lydia are unimaginable, yet Atwood imagines her inner life with such nuance and complexity that she easily becomes the most believable of the narrators. Her backstory is especially gratifying. How could a family court judge who once wielded a gavel become the ur-Aunt of Gilead, threatening insubordinate Handmaids with a cattle prod? Recording her testimony in a sheath of papers she secretes in a copy of John Henry Newman’s A Defence of One’s Life, Aunt Lydia writes without knowing whether anyone will read her own life’s defense, let alone accept it.

Agnes Jemima is fascinating as an example of an (almost) successfully indoctrinated daughter of the patriarchal state. But Atwood leaves a sliver of space for readers to feel sorry for the young woman as the hairline fractures in her worldview give way to cracks that can no longer be ignored. She stumbles into a startling feminist critique:

The adult female body was one big booby trap as far as I could tell. If there was a hole, something was bound to be shoved into it and something else was bound to come out, and that went for any kind of hole: a hole in a wall, a hole in a mountain, a hole in the ground. There were so many things that could be done to it or go wrong with it, this adult female body, that I was left feeling I would be better off without it.

Agnes Jemima’s evolving faith in God and Gilead presents the most theologically provocative material in the novel. When she finally encounters the Bible, a friend warns her that it doesn’t say what Gilead says it does. She is deeply rattled to uncover the vast discrepancies between text and interpretation of text—an experience that is surely familiar to many.

Jade, the sole character raised just beyond the grip of Gilead, is the least compelling of the narrators. Her responses to tragedies and revelations are jarringly tepid. Her grief is cursory, her anger one-dimensional. I’m not convinced that Atwood instilled these character flaws in Jade on purpose. I suspect they may be the consequence of a slightly underbaked novel.

And here is where I must make my own confession: despite the extraordinary anticipation and celebration surrounding the publication of The Testaments, I have yet to shake my astonishment—and unease—that Atwood elected to make fiction about Gilead again. It’s her prerogative, of course. She created this terrible dystopia, and if she wants to tell me everything I ever wanted to know about Aunt Lydia, it’s not like I’m going to complain. But the weak nature of Jade’s character strengthens my suspicions that it might not have actually been a great idea to revisit Gilead after all.

Early in the novel readers learn that Jade is, in fact, Baby Nicole, a character conceived not by Atwood but by the folks over at Hulu (which is ironic, since Jade’s parentage is also a matter of debate in the novel). Perhaps the mixed-media world Atwood is cocreating with Hulu is a legitimate expression of art in the postmodern era, but it all seems a bit too meta: it draws attention away from Gilead and toward the awkwardness of creating a sequel after the keys to the kingdom have been handed over to a television studio.

This awkwardness is surmountable. The implications of the zeitgeist are more complicated. In a recent column for the New York Times, Michelle Goldberg points to the fundamental problem with The Testaments: it anachronistically presumes that knowing and speaking the truth about our political system will set us free. “Imagine: a world where exposing the misdeeds of a regime could unravel it,” she writes.

We read and watch the unfolding stories of Gilead in a context that remains alarmingly abnormal, a context in which damning revelations are shrugged off and all but forgotten. Inasmuch as our current political situation seems immune to the truth, reality might be even more dystopian than Atwood’s dystopian fantasy.