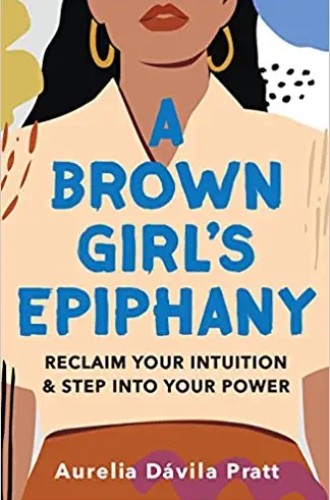

Aurelia Dávila Pratt’s paths to healing

Her powerful debut resonates deeply with my lifelong labor to honor my name and my voice.

“Ah-suh-VAY-duh Hot-puh-TAY-duh” at roll call drew guffaws, a reminder that we were the only Acevedos in our rural northwest Georgia phone book. My teacher’s rhyme made my insides flinch while I sat very still at my wooden desk, the lone sixth grader with café con leche skin.

This memory resurfaced when I was just a few pages into Aurelia Dávila Pratt’s new book. At five, living in rural north Louisiana, she began going by her family nickname Rae-Rae at T-ball practice because her coaches had trouble with her first name. In high school, a cheerleader on her squad truncated Aurelia to Uh-ray, saying, “I’m just gonna call you ‘Uh-ray’ because your name is too long.”

Pratt’s powerful debut resonates deeply with my lifelong labor to honor my name and my voice. Christian notions of sin traditionally identify with the male experience of “pride, will-to-power, exploitation, self-assertiveness, and the treatment of others as objects,” notes theologian Valerie Saiving Goldstein in “The Human Situation,” and pride’s historically preached antidote is selflessness. Hence, women are harmed in a system where, as Jungian psychoanalyst Ann Ulanov suggests in Receiving Woman, pride has one meaning for those at the top of society and another for those on the bottom of patriarchal systems: “For a woman sin is not pride, an exaltation of self, but a refusal to claim the self God has given.”