Aimee Nezhukumatathil shows us the worlds she sees

The poet’s collection of essays is so vivid, we can smell, hear, taste, touch, and see her rapture.

In a year when many of us have had to limit our travel to backyards and neighborhood parks, Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s self-reflective essays promise that even there, our natural observations can attend to our deep worries, our seasoned griefs, and our unmitigated joys. We can revisit old trips anew. We can dream forward.

Nezhukumatathil takes us to the middle of the great inland freshwater sea, Lake Superior, to a spot where migrating butterflies take a sharp turn—baffling many until a geologist recognizes an ancient mountain beneath the lake floor. Our poet describes these monarch moves as “the loneliest kind of memory.” She puts her arm around us, focuses our attention just right, and with humility excavates our deepest landscapes so that we are lonely no more.

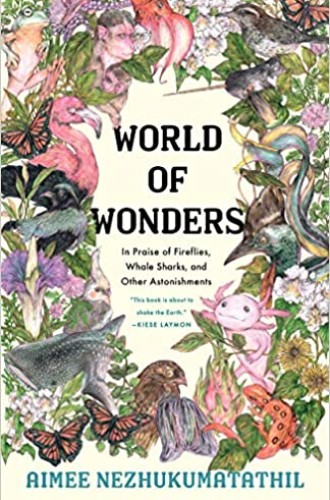

In this book there are narwhals and thigmonasty, vampire squids and monsoons. There are axolotls with serene visages that “don’t seem to ever develop scar tissue to hide damage from a wound.” Like all the natural phenomena Nezhukumatathil collects for us, these amphibians are more than just docile, smiling creatures. They map onto human behaviors, at times with searing vindication.